From automotive spare parts to satellite antennas, applications for 3D printed aluminum parts are expanding due to an uptick in the adoption of new aluminum materials developed specifically for additive manufacturing. There are also more 3D printer options and services on the market to deliver pure and alloy aluminum parts.

3D printed aluminum alloys often have better material properties than conventionally manufactured aluminum and parts made from these alloys can feature the complex geometries only possible with additive manufacturing (AM).

NASA’s Moon to Mars objectives require the capability to send more cargo to deep space destinations. This novel aluminum alloy could play an instrumental role in this by enabling the manufacturing of lightweight rocket components capable of withstanding high structural loads.

In October, the US Navy announced that it used a containerised liquid metal 3D printer to produce functional parts in situ aboard the USS San Diego. The aluminum parts were subsequently evaluated for quality and performance, with results indicating the components were fully functional for their intended applications.

Scott Bike Components recently debuted a novel handlebar (pictured above) design at the bicycle expo Eurobike 2024 that housed the brake cables inside through internal channels. The 3D printed handlebar was made from a stronger aluminum alloy called Aluminum 6061 and 3D printed using a metal laser powder bed fusion machine from Trumpf.

3D printed aluminum parts landed on the Moon as part of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Smart Lander. The shock absorber structures found on the tip of each lander leg were designed to deform on impact with the surface to soften the landing, yet needed to be super lightweight for the travel.

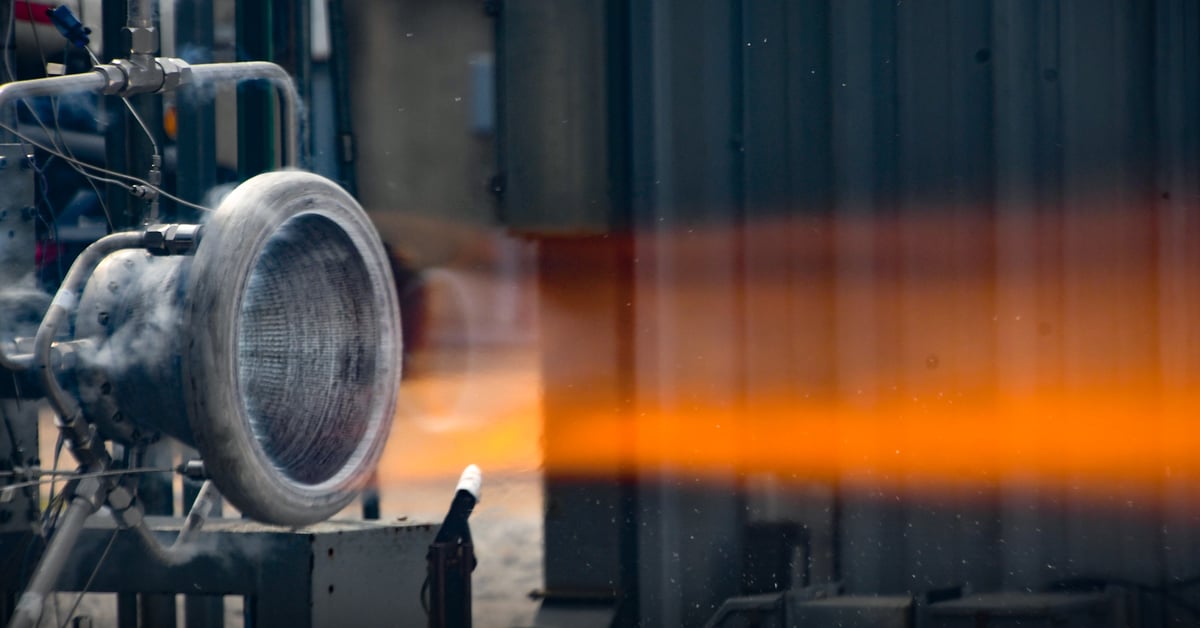

In November, 3D printer maker Eplus3D and Leap 71, a developer of AI-based engineering technology headquartered in Dubai, designed and 3D printed an aluminum rocket thruster standing more than 1.3 metres tall that is believed to be the world’s largest single-piece additively manufactured rocket thruster. Eplus3D manufactured it in one uninterrupted build process that lasted 354 hours.

A more down-to-earth example of 3D printed aluminum’s strength can be seen in the “world’s fastest bike”, which was 3D printed in Scalmalloy, a high-performance scandium, aluminum, and magnesium alloy developed by material maker APWorks specifically for additive manufacturing. This ultra-lightweight 3D printed bike frame (3D printed on a large format EOS M400 machine) contributed to Filippo Ganna’s record-breaking speed (56,8 k/h) at the 2022 Hour Record in Switzerland.

Also turning to 3D printed aluminum, Airbus Helicopters announced new plans to expand its additive manufacturing capabilities by establishing a new 3D printing centre in Donauwörth, Germany, that will house more machines by Trumpf, in addition to the ones already used by Airbus Helicopters to produce structural components made of high-strength aluminum and titanium.

Airbus Helicopters will initially use the new facility to produce components for the electric-powered CityAirbus concept and an experimental high-speed Racer helicopter, as well parts for the Airbus A350 and A320 passenger aircraft, among others.

Manufacturers large and small are turning to 3D printed aluminum, so let’s take a look at how printer makers and material manufacturers are working together to drive new applications for 3D printed aluminum.

Advantages of 3D Printing Aluminum

Aluminum alloys feature good chemical resistance, are very lightweight, and feature one of the best strength-to-weight ratios of any metal. It’s the choice of many in the aerospace and automotive industry for its ability to withstand harsh conditions.

There are numerous reasons aluminum is an ideal material for a wide range of applications, but couple it with the unique benefits that 3D printing can deliver, and it’s an even better choice.

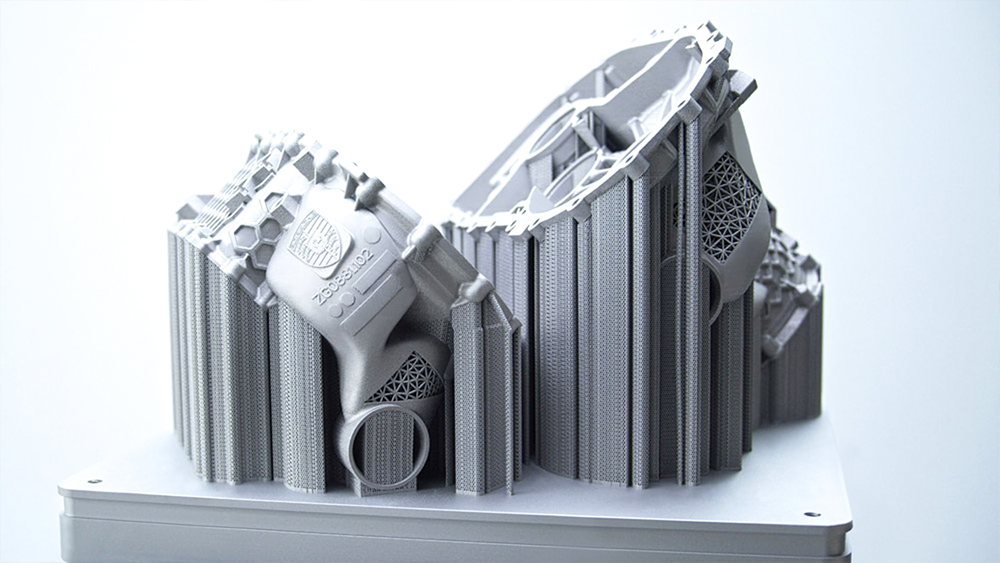

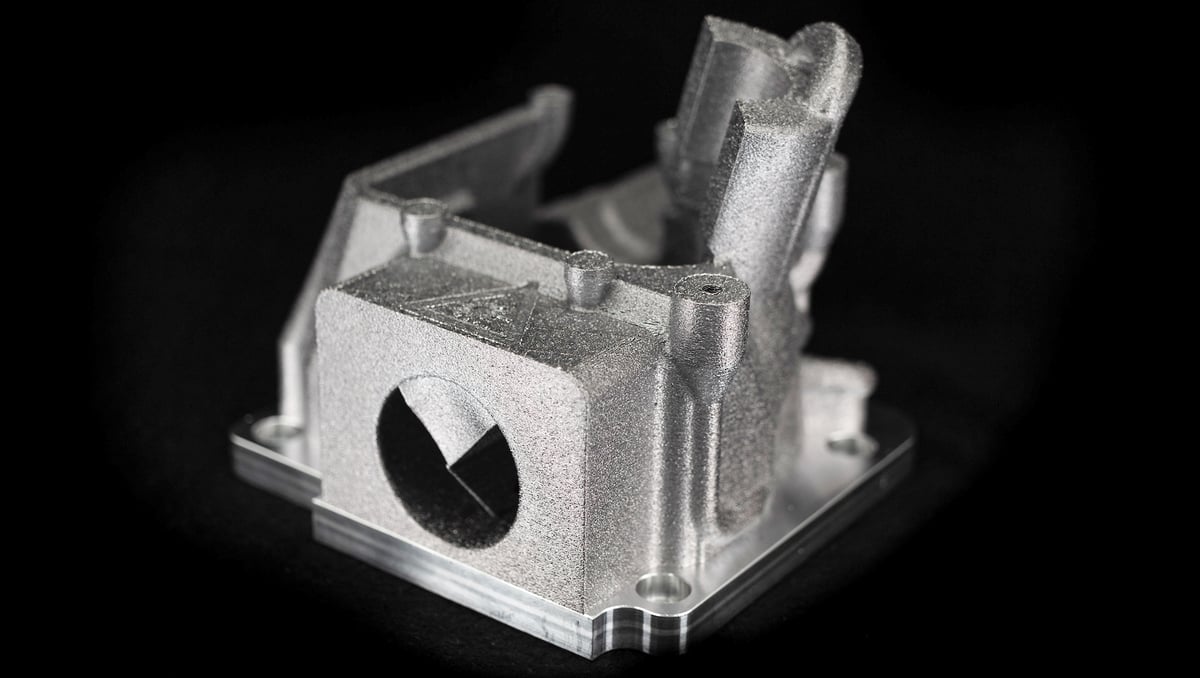

One of the biggest advantages of 3D printing in aluminum, or any metal for that matter, is that you can create parts with internal channels and features that aren’t possible to manufacture any other way. You also can print a multi-part assembly as one unit, drastically cutting down on manufacturing and assembly time, and developing a more efficient part overall.

3D printing also does not create much waste. When you’re working with expensive raw materials, anything you can do to minimize waste is a big plus. This is particularly interesting for the aerospace industry, which constantly strives to improve its “buy-to-fly” ratio, the weight of purchased raw material compared to final part weight. This ratio is crucial for assessing the efficiency of manufacturing processes, as a higher ratio indicates more material waste during production.

Casting or machining aluminum often has higher production costs (especially for low volumes) and uses more energy during fabrication. There’s also the additional cost of first producing tooling or molding for the traditional processes.

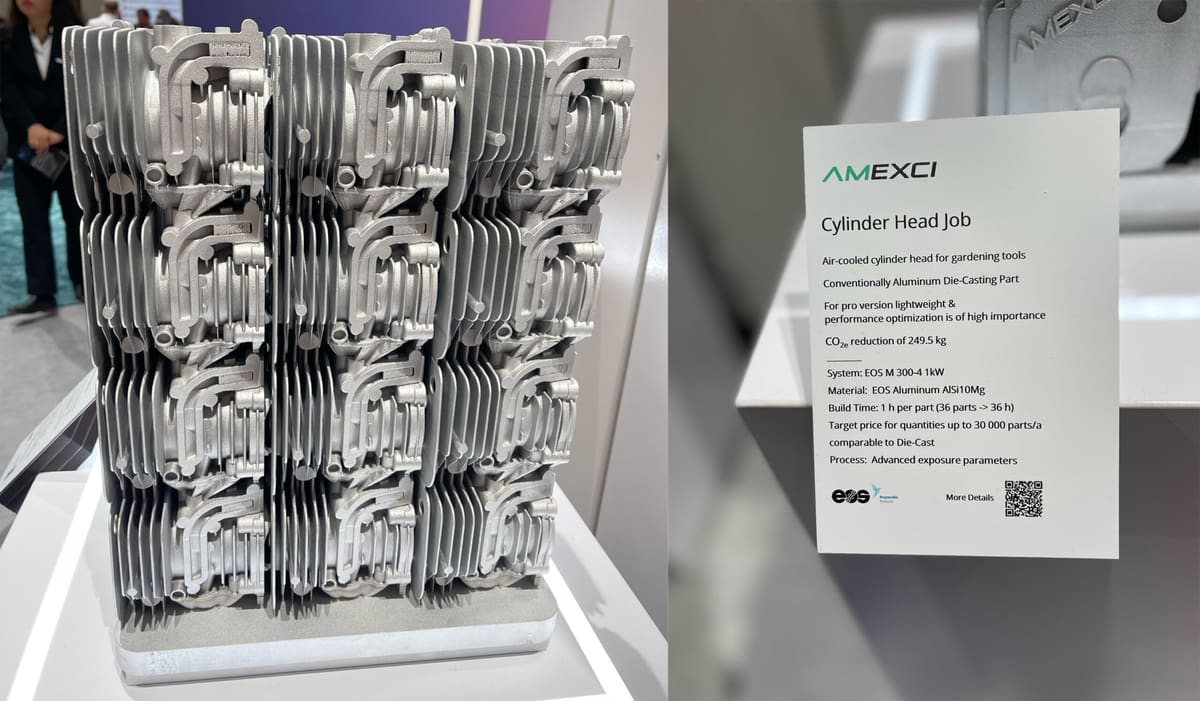

In addition to these advantages, 3D printing aluminum is also the economical choice when you need just one spare part or a low volume of products. Additive manufacturers can produce low-volume and custom parts quickly and affordably and emerging technology continues to make both larger production runs and lower operational costs a reality.

How to 3D Print Aluminum

Nearly every metal 3D printing technology can process aluminum, with the differences among them being speed, size, level of detail, and the type and cost of the feedstock. Below are six technologies, but there are some lesser-used others we detail below.

- Fused deposition modeling (FDM)

- Laser powder bed fusion (LPBF)

- Electron beam melting (EBM)

- Metal Binder Jetting (MBJ)

- Cold Spray

- Wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM)

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM)

For FDM, only two companies currently offer an aluminum metal filament (The Virtual Foundry and Zetamix). This method requires post-processing steps — debinding and sintering in a furnace — to achieve a more than 90% metal part. It’s the cheapest way to get an aluminum part since aluminum filament will work on most desktop FDM printers, but these are most commonly used for decorative and prototype metal parts rather than functional ones.

Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF)

Top Aluminum LPBF 3D Printers

Electron Beam Melting (EBM)

EBM is a similar process to LPBF, but uses an electron beam instead of a laser. The high process temperature of the electron beam results in slower cooling of the single layers and, therefore, coarser microstructure compared to LPBF. Pure aluminum is not compatible with EBM, but titanium-aluminum alloys are.

Top Aluminum Alloy EBM 3D Printers

- QBEAM Aero350

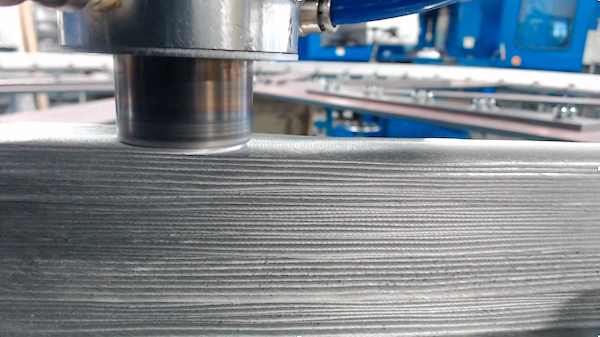

Cold Spray & Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM)

Cold spray and WAAM technologies are used to quickly create net-shape large aluminum parts that are then often machined to finer tolerances. This method is far more economical than casting for single, unique parts used in heavy industry.

Top Aluminum Cold Spray 3D Printers

Top Aluminum WAAM 3D Printers

- ALM3D

- MX3D

- Gefertec

- WAAM3D

- Caracol

Metal Binder Jetting

Metal binder jetting for aluminum is the technology option for fast printing of medium to large volumes of parts. This technology requires post-processing. There are three major manufacturers making metal binder jetting 3D printers, but only one prints with aluminum, Desktop Metal.

Top Aluminum Binder Jet 3D Printers

- Desktop Metal’s X-Series , Production System, & Production System P-1 (with Reactive Safety Kit)

Specialty Aluminum Technologies

One specialty technology involves extruding molten aluminum. Called molten direct energy deposition (molten DED) or liquid metal jetting, among other terms, this technology differs from metal extrusion 3D printing in that the extrusion versions use a metal feedstock with a bit of polymer inside to make the metal extrudable. The polymer is then removed in the heat treatment stage.

Molten DED, on the other hand, uses a pure metal. It’s available from 3D machine makers Grob, Valcun, and ADDiTec. Xerox had offered the technology on its ElemX 3D printer, which is currently installed at select US military installations, but sold it to ADDiTec. The benefit of this approach is that there’s no hazardous metal powder to work with and the finished prints do not require any post-processing.

Another specialty technology for aluminum at production volumes is in development from start-up called Alloy Enterprises. The company uses a type of sheet lamination 3D printing process that uses as its feedstock sheets of aluminum. It’s not clear whether Alloy Enterprises will offer their technology as a machine or a service.

In a category of its own, yet similar to molten DED, one company called Meld uses friction energy deposition (also called friction stir energy deposition). FED is a solid-state process, meaning the material does not reach the melting temperature during printing so it produces parts with low residual stresses and full density, the company says, using significantly lower energy than more conventional fusion-based processes. FED is also a single-step process that does not require sintering or post processing. The process has potential for quick metal manufacturing without hazardous metal powders or heat.

Advanced Aluminum Materials

In 2024 alone, there has been considerable R&D effort in aluminum alloys for additive manufacturing. Not only about the launch of new aluminum alloys for 3D printing but also 3D printers now compatible with aluminum. For example, BLT launched new high-strength aluminium alloy, BLT-AlAM500, specifically designed for aerospace applications while Elementum 3D launched A5083-RAM2, a high-strength aluminium alloy that does not require any post-build heat treatment.

In the early days of AM, engineers had challenges working with aluminum, but things have changed. New high-performance aluminums and alloys have been crafted specifically for 3D printing processes that exhibit the traditional characteristics that manufacturers today require. These materials are particularly tuned to take advantage of the unique melting processes of laser and electron beam additive manufacturing.

Some new start-ups have arrived with proprietary atomization techniques to produce high-performance aluminum alloy powder specifically for 3D printing. The list of “printable” metal materials has doubled in the last three years, dramatically expanding the number of possible applications where users can leverage additive manufacturing.

Special Aluminums for 3D Printing

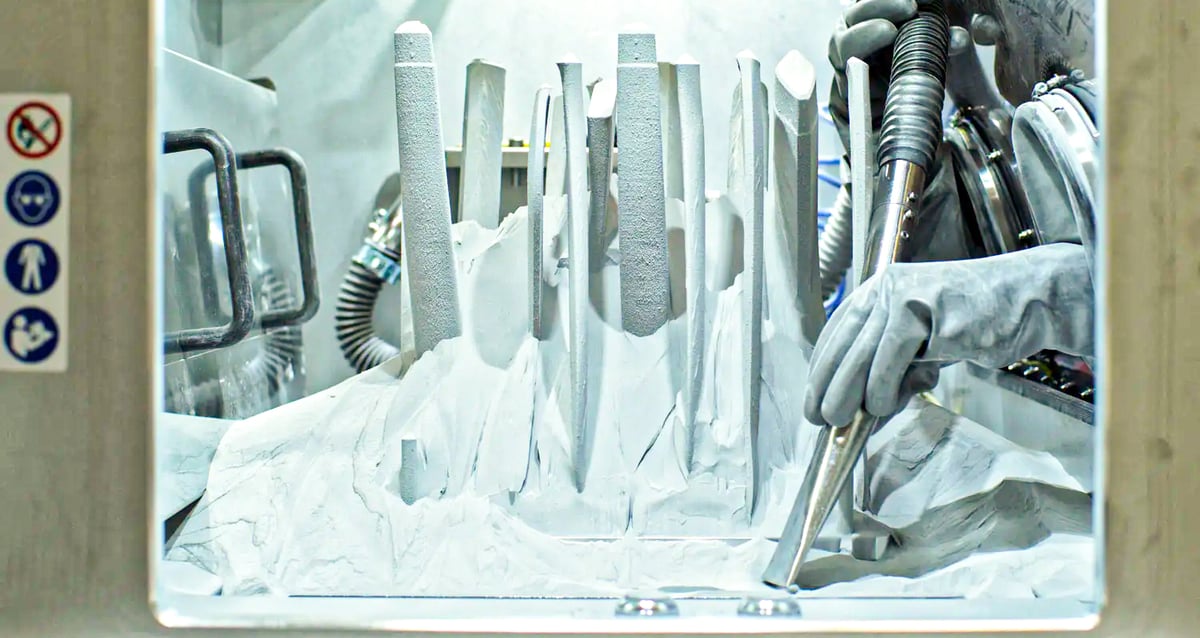

- NExP-1, launched in late 2022, by materials company Equispheres, is a non-explosible aluminum alloy feedstock for additive manufacturing that reduces the hazards associated with the day-to-day handling of materials for 3D printing. Equispheres also says its Performance AlSi10Mg powder designed for additive manufacturing, was able to reduce printing time by more than 60% when printing a complex equipment component on an Aconity3D laser powder bed fusion 3D printer.

- Scalmalloy, developed by additive manufacturing company APWorks specifically for 3D printing, is the highest strength AM processable aluminum alloy, the company says. It’s used in aerospace and motorsports to stand in for high-strength 7000 series aluminum.

- A20X aluminum powder was explicitly developed for additive manufacturing by Aluminium Materials Technologies, now a part of Eckart Group. The company says this special alloy designed for aerospace applications can produce significantly lighter components than conventional aluminums.

- Elementum 3D offers gas-atomized aluminum alloy additive manufacturing feedstock powders, including enhanced versions of traditional aluminum alloys and advanced dispersion-strengthened aluminum powders enabled by the company’s proprietary Reactive Additive Manufacturing (RAM) process. The RAM process makes previously un-weldable and, therefore, unprintable aluminum alloys available for metal 3D printing as feedstock powders.

- EOS Aluminium Al2139 AM is a proprietary aluminum alloy from printer and material maker EOS engineered specifically for additive manufacturing to offer performance in elevated temperatures up to 200ºC. Launched in 2021, the alloy is designed to give EOS customers an opportunity to significantly reduce the weight of manufactured parts without compromising strength (tensile strength around 500 MPa when heat treated).

- Aheadd is a collection of two aluminum powders from material company Constellium optimized for the laser powder bed fusion processes. Aheadd CP1 offers many benefits, including thermal and electrical conductivity approaching that of pure aluminum, high ductility and excellent surface finishing characteristics. This alloy is also a cost-effective alternative for other AM applications due to its very high printing speed and simplified post-processing, which make Aheadd CP1 the solution of choice both for rapid prototyping and series production.

- S220 AM is a new aluminum alloy for laser powder bed fusion launched in 2022 by Swedish company Granges Powder Metallurgy. S220 aluminum alloy offers high silicon content, low density, and a low coefficient of thermal expansion. Currently only available as a service.

- CustAlloy aluminum from Kymera’s ECKA Granules is specifically designed for laser powder bed fusion and is particularly beneficial in automotive applications, the company says, because it does not break or crack as quickly as traditional aluminum, making crash-relevant applications possible. This patented Al-Si-Mg-based alloy is heat treatable to offer high strength or exceptional ductility, depending on the final application.

Standard Manufacturing Aluminums

Many of the current aluminum alloys for 3D printing are simple casting alloys, such as AlSi10Mg. These aluminum alloys are not particularly strong, nor can they manage high temperatures. Still, their mechanical properties are suitable for a wide range of applications and the material is “weldable” and, therefore, can be used in 3D printing without cracking. The properties of these materials may be all some companies are looking for in metal 3D printing, but others, especially aerospace and advanced manufacturing, need more.

While there are several different types of aluminum alloys on the market, here are some of the more common ones being used in AM.

- AISi10Mg is the most common aluminum alloy and features solid strength, hardness, and dynamic properties. Its light weight also supports good thermal properties and has strong buildability for use in challenging geometries. Uses include housings, ductwork, engine parts, and production tools.

- AlSi7Mg0 combines aluminum, silicon, and a small amount of magnesium to create a highly durable and lightweight allow suitable for fine objects and complex geometries. It’s used in applications that require a strength/mass ratio as well as good thermal properties.

- Al 6061 & Al 7075. 3D manufacturers are starting to have success with printing using 6061 and 7075, which were previously thought not to be conducive to the AM process. Merging nanoparticles is showing progress.

Alloys in the 6000 series have properties that make them one of the most popular traditional manufacturing of electrical or electronic parts. They are ductile with high thermal conductivity, electrical conductivity, and corrosion-resistant. The 6061 is a precipitation-hardened aluminum containing magnesium and silicon.

7000 series alloy powders have a high zinc content, are known for excellent mechanical properties for higher strength and are heat treatable. 7075 is most commonly used in highly-stressed structural parts, such as aircraft parts, and is stronger than many standard structural steels.

Order Aluminum 3D Printed Parts

Investing in a metal 3D printer is no small decision, and part of any good due diligence is ordering sample parts. You can order these from the manufacturer, but many printer manufacturers on this list also offer print-on-demand services. For smaller projects, one-offs, and tests, outsourcing your 3D prints to a metal 3D printing service can dramatically save on the capital cost and overhead of operating your own system.

There’s a growing number of contract manufacturers with fleets of metal 3D printers ready to custom print your part whether it’s a prototype, a final functional part, a unique spare part, or a work of art. With dozens of potential service providers to chose from, you can spend weeks tracking down the best price and delivery options. Fortunately, there are a few marketplaces of 3D print services, such as Craftcloud, where you simply upload your 3D model and receive multiple quotes from suppliers from which you choose the best fit.

Lead image source: Clockwise: 3D Systems designed by nTopology, Constellium Powders, One Click Metal, dog by Cole Mathisen with Mass Finishing Inc., EOS.

License: The text of "Complete Guide to Aluminum 3D Printing" by All3DP Pro is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.