The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic is slowly but surely affecting all aspects of daily life. For many countries, this means closed borders, social distancing, and the closure of places of work, worship, and recreation.

Parallel to the disturbance to public life, is the chaos wreaked on healthcare services by the increased number of patients admitted to overburdened hospitals. Often requiring a particular type of ventilator for life-support – Covid-19 is a respiratory virus – the sudden spike in demand for these machines, not to mention the mountain of personal protective equipment (PPE) required to protect medical workers, has stretched supply chains and the hospitals using them to a breaking point.

Here are the ways 3D printing and the ingenuity of companies and individuals that use it could, and in some cases already have assisted with stop-gap measures during the Covid-19 crisis.

(Lead image credit: Carbon, via Twitter)

Latest News

Here’s some of the latest news on how 3D printing is making a difference in the fight against the spread of Covid-19.

Canada Regulates Production of Face Shields

Throughout our weeks of watching the herculean effort to plug the PPE supply gap, we’ve seen comments from individuals that have seen their efforts turned away (rightly or wrongly – we couldn’t possibly say.) Similarly, debate continues for some about whether medical institutions will even accept the 3D printed solutions. Obviously, there is a resounding answer to this, in the tens and hundreds of thousands of donations making it to hospitals and medical centers the world over. Needs must.

In Canada there is, for now, less ambiguity about the status of maker-made shields and similar PPE, with two pathways of regulatory authorization applying to the ‘sale’ (or rather, transferal – no money need change hands) of 3D printed ‘Class 1’ devices.

In short, maker-made face shields and similar ‘Class 1’ personal protective equipment are only permitted when the manufacturer is in possession of a Medical Device Establishment License (MDEL), or authorization under the recently introduced Interim Order (which came into being on March 18, 2020). The latter is a trimmed back license application that the government aims to fast-track within 24-hours of application.

Minimum specifications apply, even in the event of “urgent” production, although this is ambiguously worded that Health Canada would “expect” the minimum specs to be incorporated into printed PPE. It’s unclear how stringently this will be vetted.

Some Canadian companies have taken the steps required to pivot, including 3D printer manufacturer Tinkerine, which has diverted its production facility to face shield production.

Prusa Puts Sterilization Methods to the Test

Following the release of its RC3 face shield design, Prusa Research has gathered valuable data on successful sterilization methods for 3D printed personal protective equipment.

In collaboration with a collection of leading Czech laboratories, research institutions and organizations, the company’s face shield underwent several rounds of sterilization using different methods and chemical agents – against Covid-19-positive solutions, among other infectious nasties.

Between Synlab, the University of Chemistry and Technology Prague, Labtech, and Czechia’s National Institute of Public Health, enough testing was conducted on Prusa Face Shields printed in Prusament PETG Orange to conclusively verify several methods and, equally important, rule out others.

It’s important to note that, clearly, these results only definitively apply to masks that match the geometry and materials of those tested. Given the Prusa Face Shield’s popularity and proliferation, the chances are that this information is relevant to a large chunk of active PPEers reading this.

We won’t go into the specific detail of the proven sterilization methods since they are explained in detail with supplementary information (that is subject to change) on the Prusa Blog. We’d be doing a disservice to paraphrase it here. Go read it there. This is too important to mess up.

Markforged Partners with Neuralphotometrics to Develop Printed Nasal Swab

Carbon fiber and metal 3D printer manufacturer Markforged has partnered with Neuralphotometrics, something of a scientific incubator (although it is also known as an optical equipment provider) to rapidly develop a 3D printable swab test to help address shortages caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

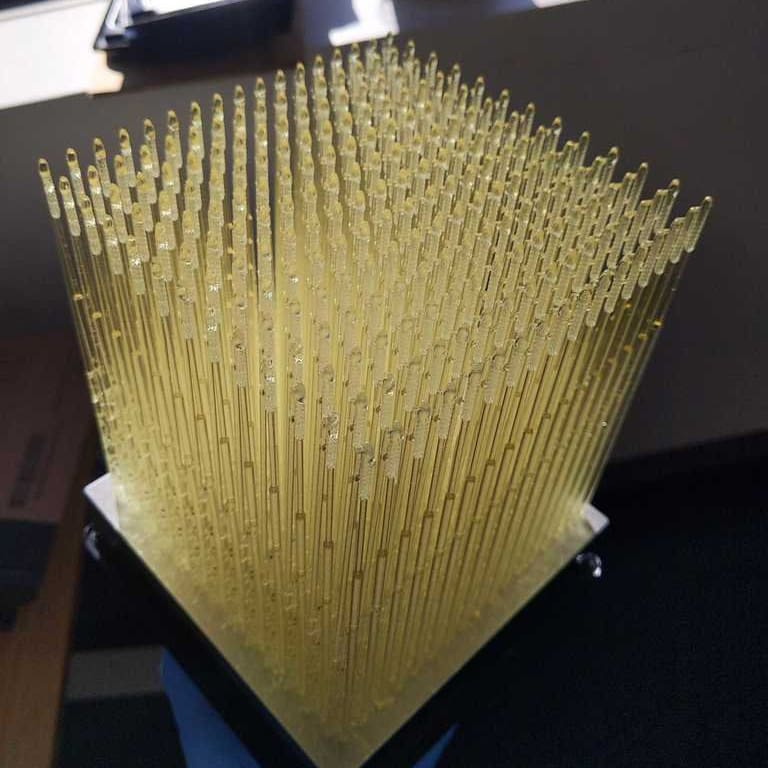

Pairing a 3D printed nylon swab base with a wrapped rayon tip, the swab underwent successful clinical validation. Printable in minutes, production of the swabs currently lies around 10,000 units daily, with the aim to increase this to 100,000.

A small startup that has improbably found itself up against the medical issues posed by the Covid-19 pandemic, Neurophotometrics has opened a GoFundMe to raise funds to scale its production capacity.

DIY: How You Can Help Fight the Virus

If you’re a maker, there are a number of initiatives already underway that you can assist in. From things like printing no-touch door handles in your own home or donating them, to giving your time and expertise to the cause, here’s how you can help.

Before starting, it’s worth noting that any of the following printables intended for use as personal protective equipment should be produced in as hygienic a manner as possible. Wear protection yourself when working on and around them – nitrile gloves, some form of face mask, even a face shield if possible. PETG is generally accepted as the better material to print with given its resistance to aggressive sterilization methods and desirable mechanical properties.

Donating to central efforts that have already gone to the effort of establishing a means of distribution is probably a smarter move than cold calling doctor’s offices yourself. Check social media for your local area to see what’s happening and who might need assistance.

Face Shields

Anyone following the buzz on social media and forums following the 3D printing community’s mobilization to do anything and everything to ease the burden on overstretched medical centers and staff will probably have noticed that simply printing a mask is not so simple. There are questions of the necessary fit, seal, not to mention being able to breathe through them and then the issue of FDM printed parts, by their very nature, are full of micro-nooks and crannies for microbial nasties to hang out in … you get the idea.

And thus, smarter folks than we have deduced that face shields, which can serve as a physical barrier from larger airborne droplets from a sneeze or a cough, are the better use of desktop 3D printing time and energy. The idea has caught on, and there are many different face shields out there, each slightly different, some undoubtedly copied, iterated, debranded, rebranded.

We previously held back from recommended any one shield over another, but as time drags on, some have undergone more clinical testing and some shape or form of official verification. Many shields have a traceable pedigree to their designs, with blog posts and versioning plain to see and the evolution of the design to suit needs shining through. Others don’t.

Depending on your location, face shields could be subject to regulation. Check ahead before rocking up to an institution to donate shields, take their advice, and be stringent about hygiene when making (see below).

Of the deafening noise of different face shields available, here’s a collection of those that appear to be accepted, adopted, in some cases even verified and recommended by institutions:

- Prusa Protective Face Shield RC3 (clinically tested – Czech Ministry of Health)

- DtM-v3.1 Face Shield (clinically tested – US National Institutes of Health)

- 3DVerkstan Protective Visor

- Budmen Industries 3D Face Shield V3

- Easy 3D Printed Face Shield (by HanochH, Coronavirusmakers.org, via Thingiverse)

There is plenty of advice about how to best produce these so as not to pose a risk to anyone you would consider passing the shields on to. Knowing that it has been approved by the Czech ministry of health, we’re directing attention to Prusa’s sensible and achievable advice.

Hands-Free Door Openers

Belgian 3D printing bureau Materialise quickly put its inhouse design talent to use during the Covid-19 crisis, designing a bolt-on door hack to make simple lever door handles hands-free.

A smart move that eliminates contact with a common transmission object at home, in public and even hospitals, the design simplifies the elbow-action we’ve all near perfected in recent weeks.

Available to download for free, the two-part print requires two long and two short screws, plus four nuts to secure them all in place. Don’t forget to print one for each side of the door.

Despite shutting its doors (as untold others are doing so during the Covid-19 pandemic), Barcelona’s CIM UPC has also released a simple home printable that can help make opening a door hands-free. Similar to Materialise’s further down this list, CIM UPC’s version is, arguably, the handier solution, requiring only cable-ties to attach to the door handle. The file is available via Youmagine.

Mask Band Relief

We can only imagine the discomfort of having an elastic strap tugging at your ears for the whole day, let alone under stressful conditions. Handily, there are insanely simple prints available that make such straps adjustable and more comfortable for the mask wearer.

There are probably many variants on this print out there, but this one has passed review in a clinical setting, and (when manufactured as instructed) has the approval of the US National Institutes of Health.

Commit and Request Resources

A number of 3D printer manufacturers, retailers, individuals, makerspaces and countless other folks deserving of credit have mobilized to commit their own resources, and organize the resources of others to be best put to use. From hyperlocal and helping their communities, to the global networks of clients in close contact with their printer’s manufacturer, there are myriad ways time, energy, and printing power are being exchanged in the fight against Covid-19.

Many are open for anyone to sign up, while others are at your disposal to find resources, materials, design talent, and machine time.

- 3D Hubs Covid-19 Manufacturing Fund – Request funding

- 3D Hubs Covid-19 Manufacturing Fund – Donate

- Carbon Gives Access to its Carbon Lattice Engine – Request access (details on link)

- MatterHackers Covid-19 Maker Response Hub – Commit resources, request assistance

- Ultimaker 3D Printing Hub – Request printing assistance and design support

- BCN3D Print Farm – Request printing assistance (email)

- Airwolf3D Print Farm – Request printing assistance (email)

- Formlabs Support Network – Request printing and design assistance, commit resources

Design an Open Source Ventilator

Further than committing printing time and materials, several open-source projects have emerged in recent days with the singular goal of developing ventilators that can be produced cheaply and locally.

Several posts covering the concept of an open-source ventilator have given wind to the idea that a crowdsourced response, channeling the kind of energy typically reserved for hackathons, could be instrumental in helping areas stricken by a spike of Covid-19 cases.

Thanks to Brent Jackson of the OpenRespirator Project, who has compiled a list in his GitHub repo, we currently know of the OpenRespirator Project, Project Open Air, and the Open Lung Low Resource Ambu-Bag Ventilator.

MIT Covid-19 Challenge

Edit: It’s not clear if this went ahead in the end. There’s no sign on the competition’s page if anything took place, and we’ve spotted a note declaring the timings as tentative. Shout out in the comments if you took part.

Starting April 3, MIT is set to hold the latest of a series of challenges designed to empower people to take action during the Covid-19 crisis. Dubbed Beat the Pandemic, the 48-hour virtual hackathon takes aim at two of the great issues posed by the ongoing pandemic: protecting vulnerable populations and supporting the health system (the latter being particularly pertinent to the 3D printing community’s current scramble to produce and donate PPE to overstretched medical and support workers.)

Open to all with no restriction to background and ability, participants will be split into teams of five or six on Friday, April 3, with the event running through the weekend to close on Sunday, April 5 in the evening (EST).

Following the event, the teams judged to have the best ideas will have the opportunity to co-develop their (open source) solution, turning it into reality.

Prusa Design Contest: Everyday Necessities for Life During a Pandemic

There are three types of objects Prusa is looking for: everyday life necessities, interactive toys, and educational items. Essentially, the goal is to help people stay creative so they don’t get too antsy while social distancing, so think things like board games, letters of the alphabet, or items you could run out of during quarantine (like clothespins, pill organizers, and handles).

One thing Prusa is not interested in is any protective gear against coronavirus.

“Untested prints could do more harm than good and actually help spread the infection instead of fighting it,” stresses the contest brief. “We will ignore such models during the contest evaluation.”

The contest will run for a total of 30 days and every 10 days during this time, Prusa will announce a winner. The first two winners will score an Original Prusa i3 MK3S kit and in the final round the same printer will also be the grand prize, but the runner up will score three Prusament spools, the third-place winner will get two Prusament spools and 20 other contestants will also get a spool each.

Get more details here.

Past News

Here’s how 3D printing companies are using their resources and expertise to fight the coronavirus pandemic.

SeeMeCNC & AtomicFilaments Injection Mold Shields for #OpShieldsUp

What started as Prusa Research’s initiative to 3D print face shields for medical workers has branched to other methods of production recently, thanks to SeeMeCNC and its production facility’s tooling and injection press machinery.

Reworking Prusa’s open source Protective Face Shield band, the folks at SeeMeCNC rejigged it to be suitable for its own injection molding machinery (consequently, it can also be 3D printed). The move means the company can form thousands of face shield bands daily.

Fuelled in part by a massive donation of PETG resin by Atomic Filament, the face shield bands are being donated to Operation Shields Up, an initiative to distribute sets of face shields by R3pkord, a California-based printer/printing accessory supplier.

The process of converting the face shield band into a mold has been teased in part on Twitter, making for fascinating viewing.

(Lead image credit: SeeMeCNC, via Twitter)

Snorkel Mask as Non-Invasive Respirator

Isinnova – the Italian company part responsible for devising 3D printable oxygen valves that were successfully used as emergency stop-gaps at a hospital in Brescia – has made a new development in its Covid-19 relief effort.

Following the coverage of the oxygen valve, Dr. Renato Favero, lead physician at a different hospital in Brescia, contacted Isinnova with the idea to adapt scuba masks, turning them into makeshift respirators.

Targeted specifically at the potential shortage of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) masks, which can be used for sub-intensive care of patients suffering from the virus, the solution arrived at by Favero is to connect full face snorkel masks to a ventilator (and wall-mounted oxygen distributors), by way of a newly designed and printed valve.

Sports equipment manufacturer Decathlon provided CAD files of its Easybreath mask for the project. Isinnova developed what it calls the Charlotte valve. Printable on an ordinary desktop printer and tested on an Isinnova employee and patient, the valve and mask are said to have performed successfully, proving their potential use in dire circumstances.

Isinnova goes to great lengths on its website to stress that its valve is for use only as an emergency solution when no other options are left, going as far as providing details on the emergency procedure for compassionate care and a declaration for prospective patients to sign before use of the device.

Carbon Gears Up with Face Shields, Micro Lattice Testing Swabs

Taking things at a clip, Silicon Valley unicorn Carbon has developed, in collaboration with Verily, a face shield for use in medical facilities, that can be printed from a number of the company’s resins.

The face shield has seen use in Bay Area hospitals and leverages the company’s extensive experience producing form-fit apparel (through its close partnership with sports brand Adidas), and development of specialist resins. The file is available to all Carbon subscribers (read: clients using its machines) via the company’s website, to make use of and assist in their local areas. The files are accompanied by the stringent requirements for the shield’s production, preparation, and care.

On a parallel track, the company has partnered with healthcare institutions including Stanford and Beth Israel medical centers to develop medical testing swabs – another crucial medical product that, in short supply, could produce bottlenecks in screening efforts.

Developed using the company’s proprietary Carbon Lattice Engine software – which has been used to develop, among other things, high-tech custom sports equipment and, perhaps most recognizably, custom midsoles for Adidas sneakers – a fast design cycle rowed through seven iterations of swabs (six passing patient testing in the process), before settling on an eighth.

Unlike the Carbon’s face shield, which is exempt from regulation and can be accepted into medical centers without hesitation, the swabs require further certification and approvals before they are likely to see field use.

Carbon’s efforts in tackling the myriad of problems the Covid-19 pandemic poses continue to manifest in other ways, including the recent opening of access to its Carbon Lattice Engine software to the public (by request via email), and an over-the-air firmware update to its printers, somehow doubling their (already fast) print speed specifically for printing the face shields.

Voodoo Manufacturing Selling Protective Face Shields

Brooklyn-based Voodoo Manufacturing runs two 3D printing factories with over 200 machines and they’ve repurposed them to help fight against Covid-19.

The company says it is working to develop personal protective equipment, replacement parts for ventilators and other needed devices.

They are selling protective face shields for $10 apiece with a minimum order of 100 units on-demand for hospitals or other organizations that need them. Voodoo Manufacturing says the price reflects the material and labor costs for production, plus “a small margin” to help keep their doors open and pay their employees.

“We are not seeking any additional profit beyond that,” they state, adding that they’re operating at “the lowest possible margin” and are taking the safety of their staff seriously.

Formlabs Developing Test Swabs

Formlab’s printers and specialist materials could prove their efficacy time and again through this crisis – perhaps first through the company’s ongoing effort to 3D print medical swabs for testing Covid-19. According to a tweet from March 22, the company has partnered with three hospitals in the US and is undergoing clinical evaluation of the parts.

Printed from the company’s Surgical Guide Resin, in testing the swabs have been printed in batches of some 300 swabs to a single Form 3 build plate. As detailed last week, the company has established a network of its users volunteering its machine time, which could mean distributed manufacturing is ready to go, should the swab receive approval for use (and the machine operators have the correct resin in stock.)

Since then, Formlabs’s CPO Dávid Lakatos reported on Twitter that they’re “waiting for final validation to print swabs for test kits,” adding they can print around 300 per platform and have about 250 printers in-house in Ohio, plus an additional 800 through their volunteer network.

Lakatos also added that the company is working on creating respiratory mask adaptors.

Prusa Protective Face Shield

Prusa Research has added its clout to the pandemic fightback, designing and prototyping a 3D printable face shield for frontline medical workers to protect their faces against the coughs and sneezes of patients in their care.

The printable – currently early on in its development at release candidate 1 (RC1) – is detailed in a lengthy but fascinating blog post on the Prusa website.

Acknowledging the problems with 3D printing parts for sensitive medical equipment (which is not impossible, but best left to the most desperate of times), and the challenges of getting printed face masks to provide the necessary fit and seal, the Prusa team instead opted to contribute with a novel, 3D printable face shield.

Turned around in three days flat – including two verifications from the Czech Ministry of Health – the mask is available to download from the PrusaPrinters website. It is recommended to print the parts in PETG.

Uniquely placed to suddenly manufacture hundreds, if not thousands of the shield brackets and bands (a separate, laser-cut sheet of PET is also needed), the Prusa print farm – as of the time of the blog post’s publication – has a fifth of its capacity working on the shields, producing 800 pieces daily. Scaled up to maximum capacity would yield 4,000 pieces daily, with headroom to grow given the company’s resources and ability to rapidly add more machines.

An initial batch of 10,000 of these early shields has been donated to the Czech Ministry of Health.

A separate, but vital note is also raised by the blog post – sterilization. The Covid-19 virus is thought to survive on plastic for up to 90 hours, meaning that it is all too easy for a printed part to become, and remain, contaminated. There are no officially verified ways of sterilizing 3D printed masks, shields, and other equipment, so it is best to err on the side of safety and treat them as one-time-use only.

Similarly, with such 3D printed emergency supplies contemplated as a short-term solution against shortages, for all the willing makers and businesses around the globe eager to help, actually producing the parts in a responsible and sterile manner matters. Good intentions alone won’t stop a contaminated printed mask or shield from potentially worsening a severely sick patient should they come into contact.

The blog post advises those producing parts they intend to donate be checked by a professional (a professional what exactly is not specified, but we would take this to mean healthcare professional you are in contact with over your contribution.)

Projects around the world that are working on proven designs such as the face shield are encouraged to contact the company via email, the intent being to share printable designs on the PrusaPrinters model repository.

Italian Hospital Uses 3D Printed Oxygen Valves

A hospital in Brescia, Italy, one of the worst-afflicted regions in Europe, has had to operate over-capacity with some 250 patients in intensive care. With each case requiring long hours of assisted breathing using a ventilator, a shortage of oxygen valves quickly became a problem.

Upon discovering the issue, Nunzia Vallini, Italian journalist and director of magazine Giornale di Brescia, connected the hospital with Isinnova, a business research and development firm that quickly made it to the hospital to inspect the valve.

Modeling the part onsite, a rough replacement was produced and in testing within 24 hours. Following initial success, some 70 more were produced with the assistance of engineers at Brescia-based industrial manufacturer, the Lonati Group.

The valves, batch produced using selective laser sintering technology, are said to be in use already, aiding the intensive care of patients fighting the virus.

A “quick and dirty” fix in a time of crisis, it demonstrates the radical agility 3D printing technology can bring to a supply chain. It’s perhaps too early to say whether stories such as Brescia will be fringe cases, or if flashpoints of the virus will make this a regular thing.

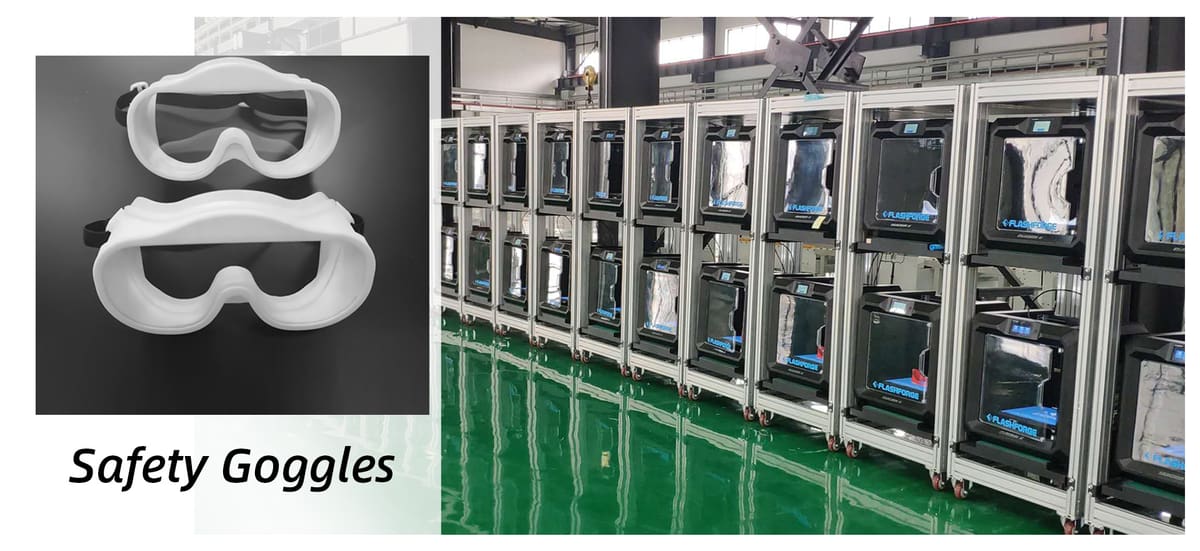

Scaling Up to Print Safety Goggles

An unnamed safety equipment manufacturer in Jinhua, China, is tackling the personal protective equipment (PPE) shortage head-on, tasking its farm of 200 Flashforge Guider 2 3D printers to produce safety goggles for frontline medical staff.

Tasking its R&D team to develop a 3D printable, mass-producible product, the company managed to finalize the goggles in a little under two weeks, a design that will result in the ability to tool up to print some 2,000 goggles daily. According to the release on Business Wire, to date, some 5,000 3D printed googles have already been donated to hospitals.

Safety & Legality

Of course, for some of these 3D printed parts used in medical devices, there’s the question of whether they’re as safe as their non-3D printed, manufacturer-approved counterparts and whether there could be any potential legal implications for jerry-rigging these life-saving devices.

Despite the success of cases like the one in Brescia, Italy and the Google sheet organizing makers’ time and resources to help, the reality is these printed parts are hugely untested. They likely could be outside of the tolerances for the machines they are paired with and will not be up to the clinical standard of production. That people’s lives hinge on the effectiveness of this printed part highlights how desperate the situation is for the communities at the heart of the pandemic.

And the legal complications of unofficially mass-producing patented parts, and who is liable should one of these printed parts fail in the care of an immunocompromised patient, are also worth giving some thought to.

Not to mention the danger of contamination with 3D printed parts – the porosity of a printed part, in addition to the Covid-19 virus being able to survive on plastic for days – make current solutions as PPE at best, only good for one-time use. Gadgets and gizmos to make hands-free operation in daily life are less risky, but for the production of protective equipment for medical workers caution is advised, as is the oversight of professionals in the making and handling of such pieces.

Regardless, the desperate situations of cities caught in the midst of this crisis have inspired makers around the world to commit their time and machines to the cause. If you find yourself in the situation to help, try to do so responsibly.

#HackThePandemic NanoHack Respirator

Update 23/03/2020: Copper3D’s website appears to be down, and there has been significant noise online criticizing the company’s mask, plan, and, well, generally poking holes in a lot of what the company has claimed of its mask. Dubious or not, we reported on it in this article, taking the apparent effort to help worldwide efforts to combat Covid-19 at face value, noting the point from Copper3D’s announcement was for others to iterate and improve the design. What we initially wrote remains below, though we have relegated its position in this article to the bottom as something of a footnote. Copper3D’s silence in the face of the criticism is somewhat damning, but perhaps the company will respond with a rebuttal to the reaction. The short of it; don’t print masks. At least, not ones that haven’t been verified or endorsed by the appropriate regulatory or medical professionals.

***

Copper 3D, a Chile/US specialist manufacturer that produces antibacterial materials, has launched what it calls NanoHack, and with it, the catchy hashtag #HackThePandemic. The NanoHack is a 3D printable face mask that could serve as an alternative to the N95 masks that are said to be in short supply.

A fast, flat print that maximizes the idea of distributed manufacturing, the mask can be printed locally and shipped flat. Thermoformed during assembly to fit the individual, the NanoHack mask looks to create a good seal around the face and provide a long-lasting alternative to disposable fabric masks that are in short supply.

It would appear that to be fully effective, the mask should be printed in Copper 3D’s PLACTIVE antimicrobial PLA filament. This certainly would shorten the risk of the plastic shell becoming contaminated. Antimicrobial material aside, there is a sealable recess that accepts makeshift filters such as cotton padding, proving at least some form of respiratory protection.

The file is freely available for all to download (ed note: link removed) and improve upon, with Copper 3D encouraging an “Open Source mindset” toward the project.

–

We’ll update this article with any other projects, solutions, and calls-to-action that emerge. If you know of any, sound off in the comments and we’ll fold them into the article where appropriate.

License: The text of "Coronavirus Crisis: 3D Printing Community Responds" by All3DP is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.