In Short(s)

Animation as a concept can be traced as far back as Paleolithic cave paintings, with bison and mammoths depicted mid-gallop, surrounded by spear-brandishing hunters. Since then, it’s fair to say it’s come a long way, helped along its course in the past 50 years by the advent of the personal computer and video sharing websites like YouTube. Animation nowadays comes in many different forms, most of them covered by either 2D or 3D as a broad description.

Defining Terms

2D animation is standardized in most cases to run at a speed of 24 frames per second. However, in some cases, due to the amount of movement required or time or budget constraints, two or four identical frames can be shown to achieve effectively 12 or 6 frames per second (fps), respectively.

3D animation, if shown on a screen, is of course still technically 2D, but it’s referred to as having three dimensions because it creates the illusion of depth – a third dimension – represented by the Z-axis. The depth in 3D animation isn’t usually created by human brainpower alone: In order to make it look convincing, computer algorithms are required to computer-generate images, hence, “CGI”.

While modern 3D animation has taken over as the dominant style from 2D, there’s still a broad spectrum of uses and applications for 2D animation, too. This article will focus on computer-based animation methods and will look at how you can animate anything your imagination conjures up with a variety of different programs.

In addition to 2D and 3D animation, we’ll also take a look at animating with CAD programs, and how 3D animation can be utilized to deliver a product idea or explanation, as well as lifelike human and organic forms.

But before we get into specific programs, let’s look a bit more closely at both 2D and 3D animation’s historical progression.

A Bit of History

2D Animation

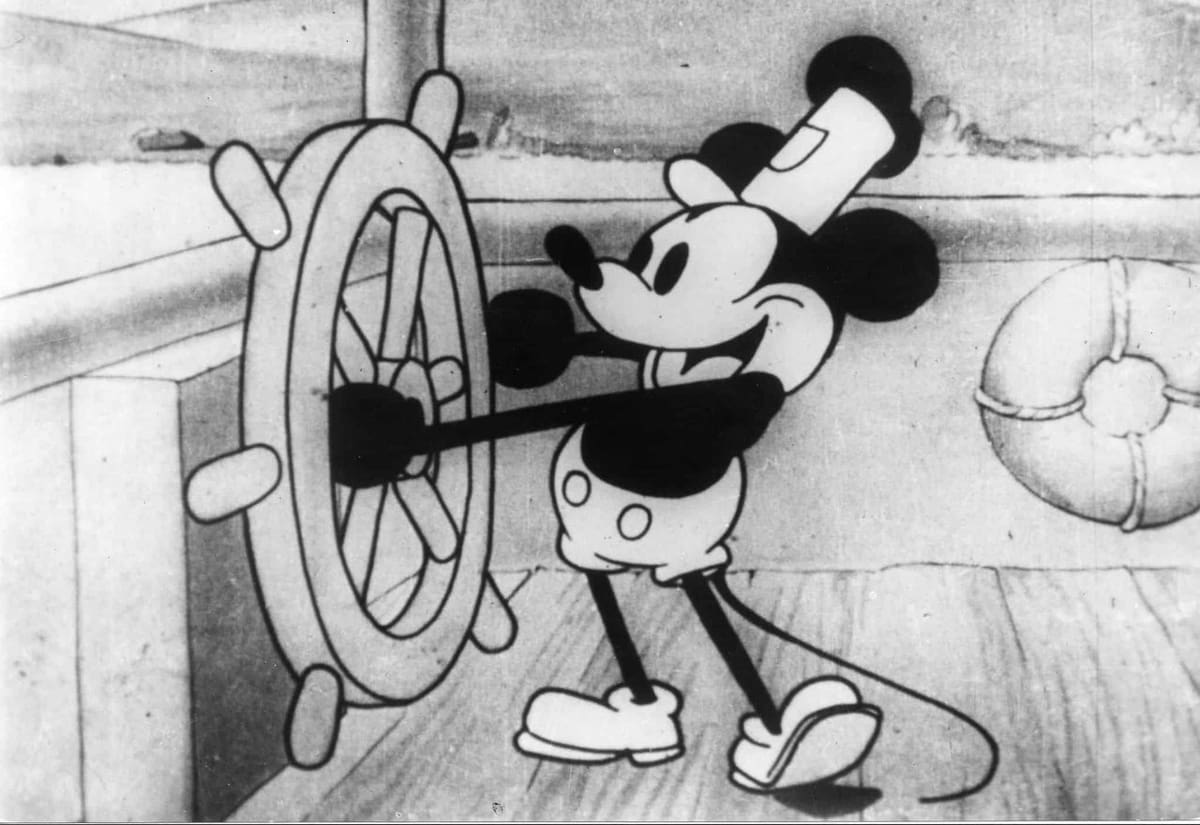

2D animation is credited to Peter Roget, who in 1824 observed how spokes on wheels appear to bend when the wheel is spun, despite obviously remaining completely physically rigid. After several unsuccessful methods of bringing drawings to life, he made a flipbook, which is ultimately responsible for animation’s wider appeal towards the end of the 19th century.

Another important figure is Georges Méliès, the subject of the book-turned-blockbuster Hugo (2011), who is often said to be the inventor of what we’d consider modern animation. He pioneered stop-motion style, which uses actual models and props that are moved in each frame, before the outbreak of WWI.

Fast Foward

Today, most 2D animation is, of course, produced with a PC – or several if it’s the work of an entire studio. Stop-motion animation remains a popular method, primarily used in children’s TV shows, anime, and the work of hobbyists or content creators.

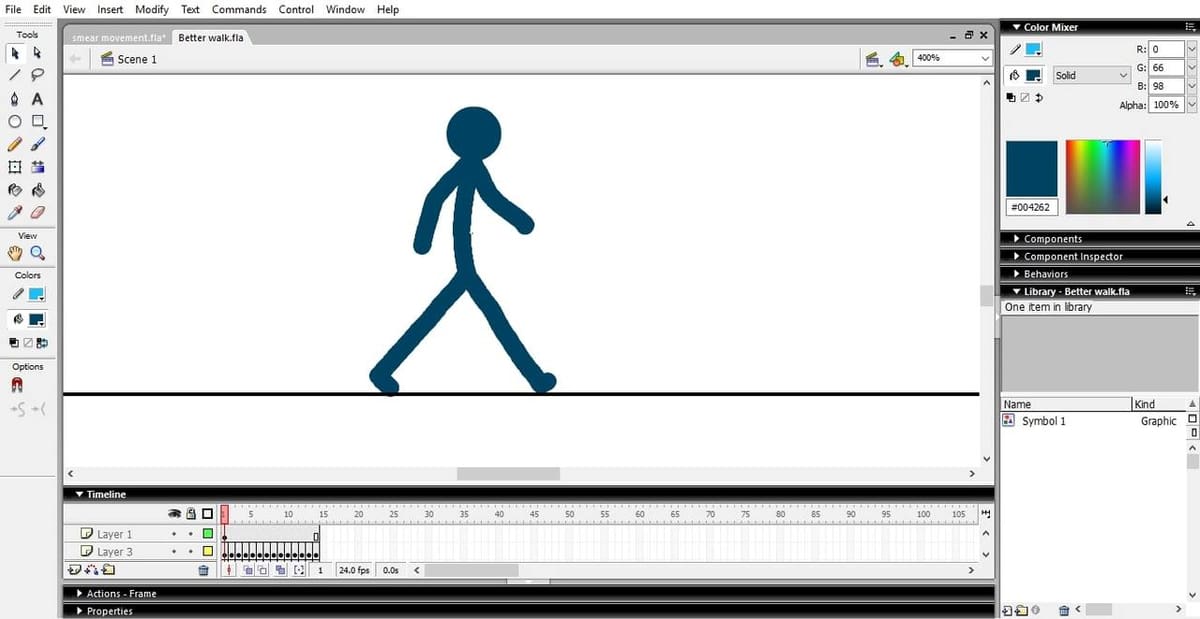

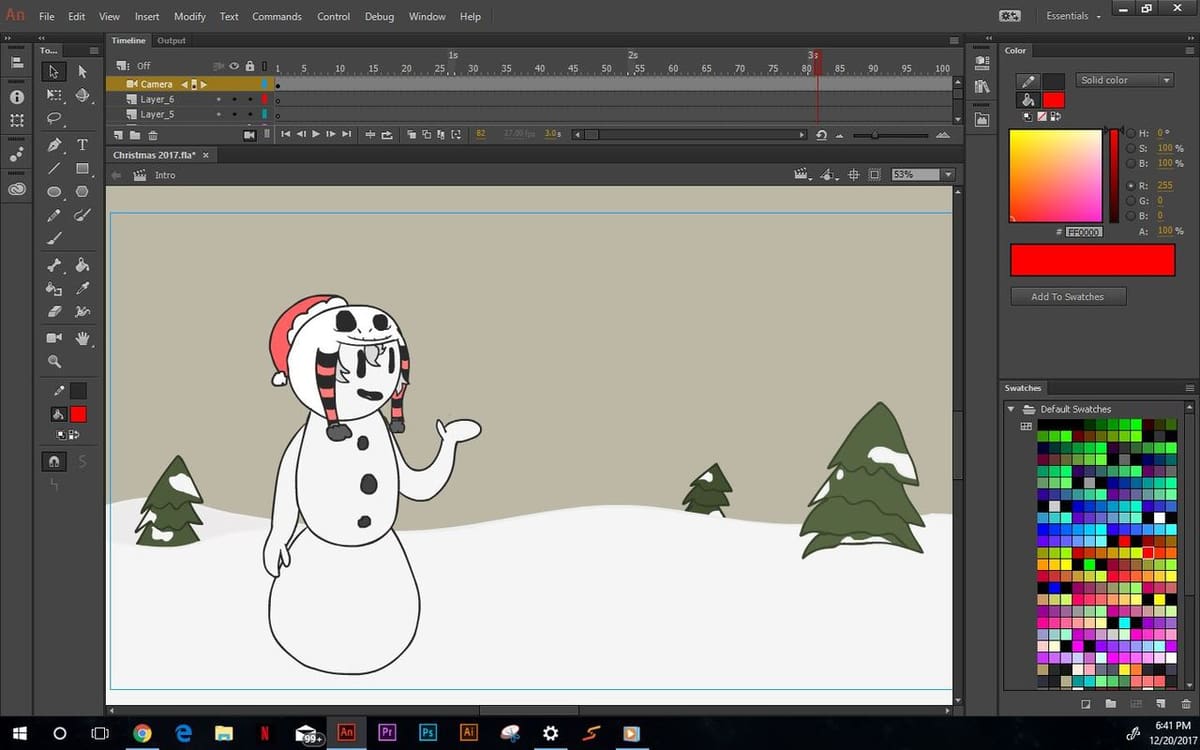

Making 2D animation can be as simple as photographing different sequential sketches to get an idea across, in a similar way to that appearing on the YouTube channel minutephysics. On the other hand, programs such as Adobe Animate (formerly Adobe Flash, Macromedia Flash, etc.) will provide the technology to create more than the relatively simplistic stop-motion sketch animations mentioned above.

The products of more professional-level animations feature in TV shows, documentary, and graphical inserts used in films and occasionally games, which are often produced with a combination of different programs (more on these programs later).

2D animation is also a big part of social media and web browsing as a whole, with animated ad banners, callouts, and moving images on webpages. Software such as the cloud-based Visme is perfect for web content design.

3D Animation

Most of what’s on TV these days, if it’s not live-action, is 3D animation. Even 2D animations, such as Family Guy and The Legend of Korra, feature some 3D animations designed to look like cartoons in their shading or block colors but create the illusion of depth, making object and landscape panning look more convincing.

3D animation has become hugely popular ever since shows like Gumby (1956) and Wallace and Gromit (1995) warmed the hearts of viewers with stop motion. In 3D animation, it comprises of photographing forms of clay models or, popularly, Lego Minifigures.

As the power of computers has developed, 3D animation techniques have progressed beyond the C-3PO vs. Chewbacca chess battle scene in Star Wars: A New Hope (1977). Now more than ever, 3D animation is being used in place of expensive props and animatronics to deliver lifelike animation to all manner of fantastic beasts, sci-fi tech, and impossible human feats.

Motion tracking bodysuits are used to capture an actor’s motion in order to overlay a lifelike alternate CGI body, a good example being Andy Serkis’ Gollum in The Lord of The Rings (2001). The technique has also had a recent resurgence in the film industry with the release of such titles as The Lego Movie (2013), which was mostly cleverly faked to appear like stop motion, and Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs (2018), which is puppet-based stop motion.

3D animation for an entire runtime is often attributed to youth-targeted television shows and films, but can also be seen in advertising and graphical additions to documentaries. Of course, 3D animation is a huge part of blockbuster video games, especially those that rely on a predetermined story to engage the player.

Creating Movement in 2D

Both 2D and 3D animation are made easier with several core tools, many of which are available in the most popular animation software programs listed at the end of this article. It must be noted, however, that some programs may be lacking in their feature set, so it’s good to know the basics of what to look out for in a fleshed-out animation program.

2D

Ultimately, two-dimensional animation is primarily created in two ways:

- Bitmap graphics refer to mostly longer animations exported in a specific resolution, intended to be played perhaps once, for the purposes of storytelling. Bitmap graphics lose clarity as they’re scaled up in size, so the export resolution is an important thing to pay attention to.

- Vector graphics mostly utilize the scalable vector graphics (SVG) file format, which does exactly what it says. Vector graphics usually encompass small animations, including webpage button rollovers and animated icons.

The biggest difference between these two formats is that vector graphics are scalable, while bitmap graphics are not. Therefore, you’ll need to consider scalability when thinking about which way to create your animation.

A good 2D animation should feature most (or all) of these:

- Onion skinning: Seeing several frames at once, placed one above the next (usually in ascending levels of transparency), in order to decide how to draw the next frame.

- Bitmap drawing: Drawing stages, props, and characters with bitmap image file formats (PNG, JPG, and GIF), which when scaled up, results in jagged edges.

- Vector drawing: Drawing stages, props, and characters with vector image file formats (SVG), which when scaled up, retain their quality because the image is saved as a collection of formulae rather than colored pixels.

- Animated raster layering: Using different animations layered on top of each other to create a unique effect (like translucent tire smoke passing in front of the wheel of a moving car). Each layer is composed of a raster (bitmap) image.

- Frame-by-frame editing: The ability to fine-tune an animation by going into each individual frame and tweaking minor details precisely.

- Bone rigging: Incredibly useful in 3D animation and 2D animation, bone rigging allows the creation of forms around a skeleton that can be manipulated using lifelike human movements and collisions without the need to translate each individual shape or body part.

Creating Movement in 3D

3D animation is technically a subcategory of CGI, though most of the time, it’s synonymous with CGI.

There are two main methods used to create 3D animation: conventional animation (the creation and manipulation of 3D models) and motion capture (actors wearing motion-capture suits).

Conventional 3D Animation

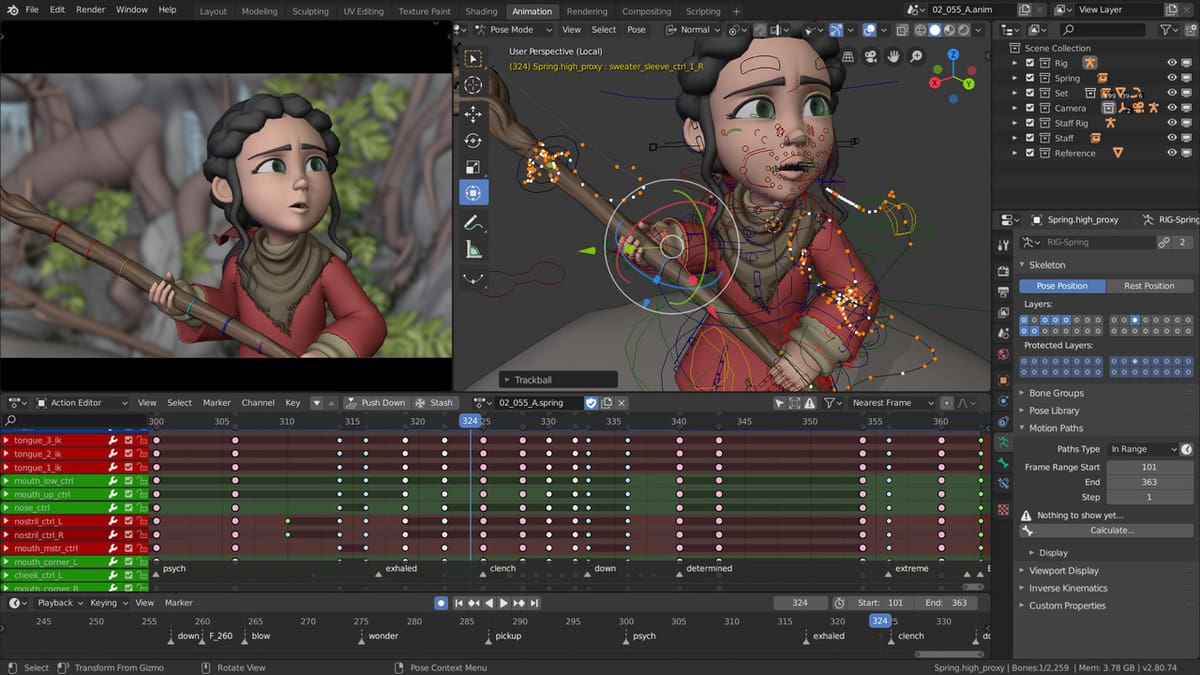

Conventional 3D animation begins with the creation of a model, typically a polygon mesh, sculpted or formed by the animator into a pose, not unlike Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

The model can then be manipulated within the scene: enlarged or shrunken, stretched or compressed, pulled or dragged, broken, torn apart, and more! Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, when a model is fixed to a bone rigging, it enables the animator to move the model in a way the viewer would expect, with body parts interacting with each other properly and realistically.

These riggings, which may resemble a skeletal form, allow the animator to pose the model, then make another pose, and bridge the gap between the poses to create movement. This is referred to as creating keyframes and eliminates the need for an animator to animate frame-by-frame, which is an incredibly time-consuming process.

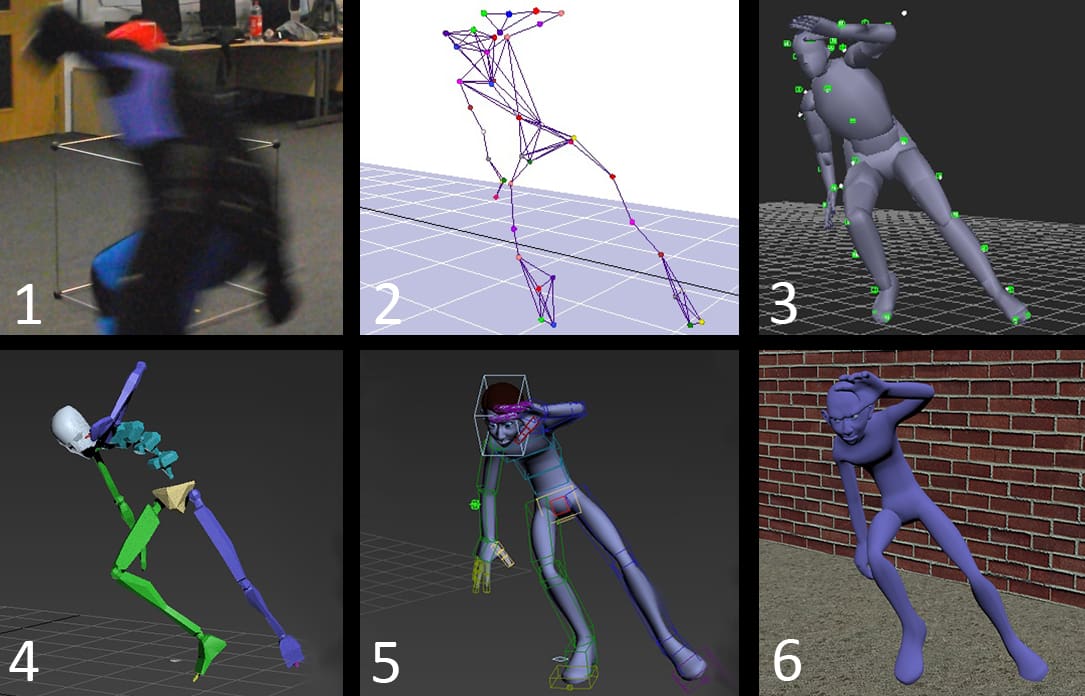

Motion Capture

Motion capture usually involves a real-world actor, in most cases a human but in some unique examples, animals have been used to capture lifelike animal movements.

The actors wear a motion capture (or “mocap”) suit covered in markers, designed so a special camera recognizes and translates the actor’s movements into a skeletal movement structure or moving organic form (like a face). Motion capture is beneficial because it enables the animator to recreate true-to-life movements, which otherwise would be very difficult to make look convincing. A prime example of this is facial tracking.

Facial Tracking

Facial tracking is where an actor’s facial expressions are precisely tracked by a dedicated camera. It’s set up to recognize the movements of dots painted onto the actor’s face as they emote.

Fantastic examples of such technology can be seen across the Marvel Cinematic Universe franchise, in particular the animation of Mark Ruffalo’s Hulk and Josh Brolin’s Thanos. Both characters rely on complex 3D models as a starting point and make use of motion capture to give the otherwise human-sized actors their beefed-up superhero (or villainous) appearances.

The character’s faces may feature enlarged musculature or slightly altered bone structure, but, beneath the CGI is a recognizable recreation of each actor’s face. This way, animated faces can effectively convey the complex emotions the characters may experience.

Other Terms & Techniques

In addition to the aforementioned methods, 3D animation requires a few other core techniques. The most important are listed below:

- Sculpting: If a mesh doesn’t already exist in a library (for example, “human female”), sculpting is the first technique employed. Sculpting can take on many forms but usually starts with a moldable block of virtual clay that’s chopped, squeezed, and changed until the organic form resembles one or more body parts.

- Facial animation: In a similar way to sculpting, facial animation relies first upon the sculpting of said face. It then progresses into facial poses (created as keyframes) attached to the rigging of a skull and jawbone or information gathered from a facial tracking camera.

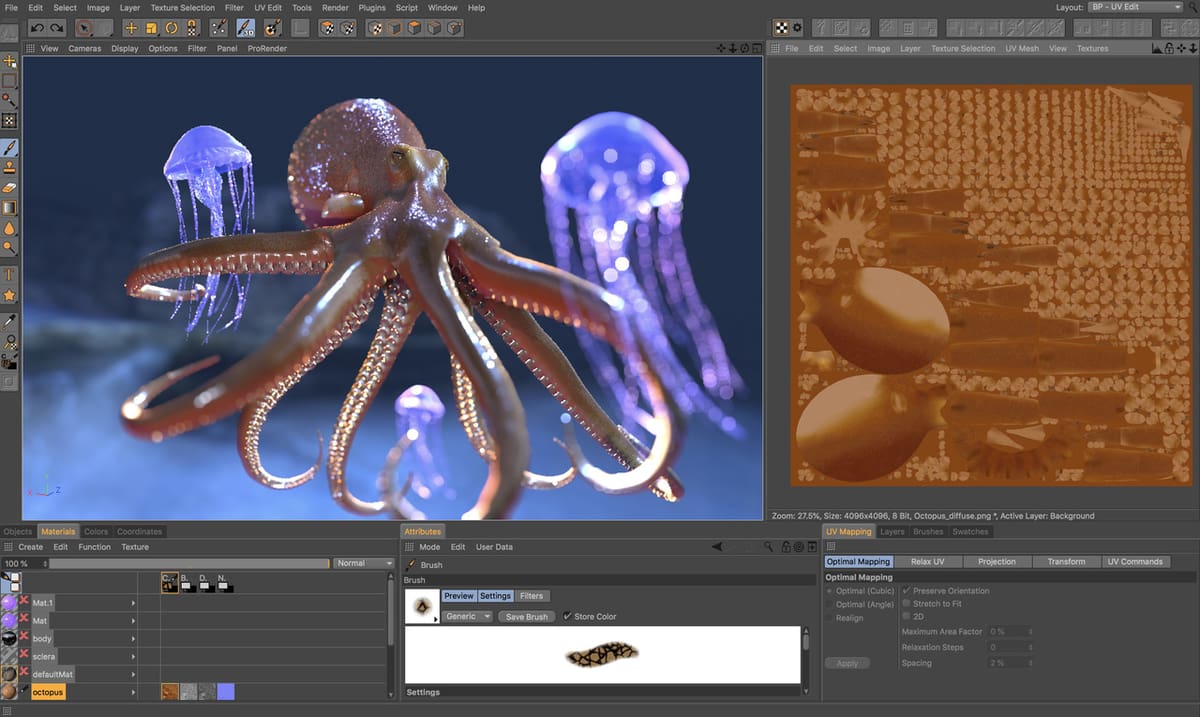

- Texturing: Once the shape of the animated model is complete, and the mesh is a closed surface, textures are added to enhance the look of the model and add detail. This can be as simple as just color or as complex as semi-transparent layers of different patterns. Such complicated textures can contribute to a lifelike appearance of, for example, freckles, veins, or dilated pores, each with their own associated properties (for example how much light they reflect or absorb or how rough they are).

- Rendering: Finally, after a scene is checked for errors, it can be rendered and made ready for export. Rendering adds light and translucency to the scene where it would’ve looked incomplete in the preview. It creates a realistic recreation of how light falls on each texture and how the textures themselves interact with each other in terms of reflectivity, absorption of light, and shadow simulation.

CAD

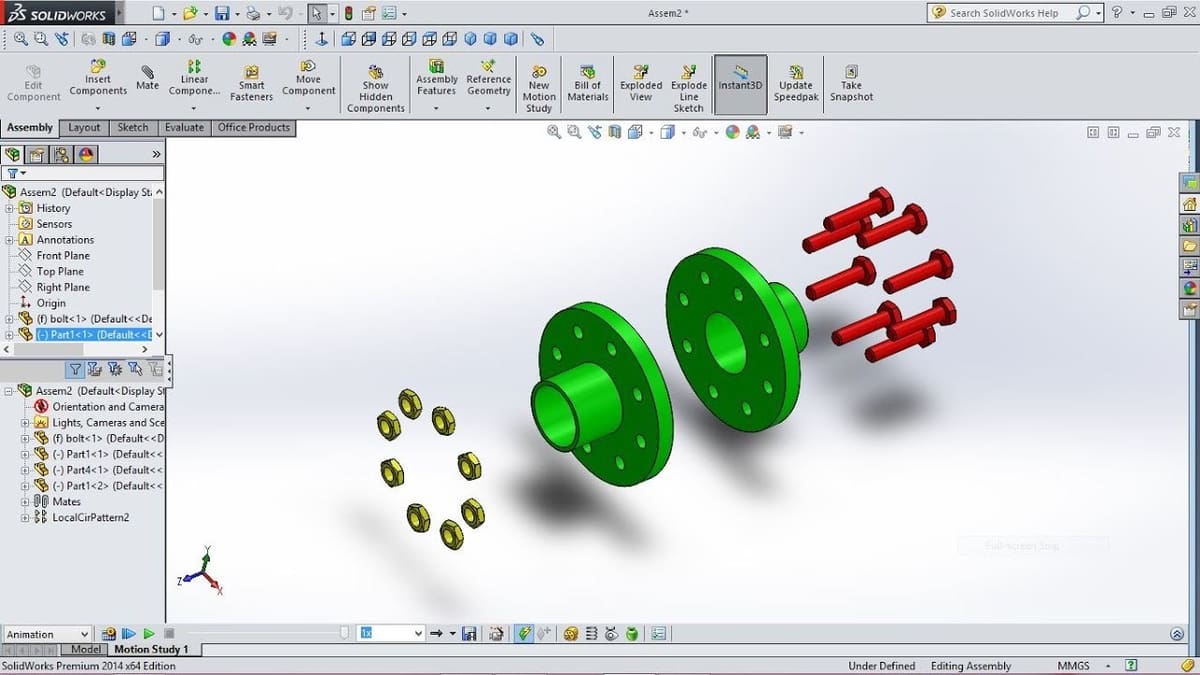

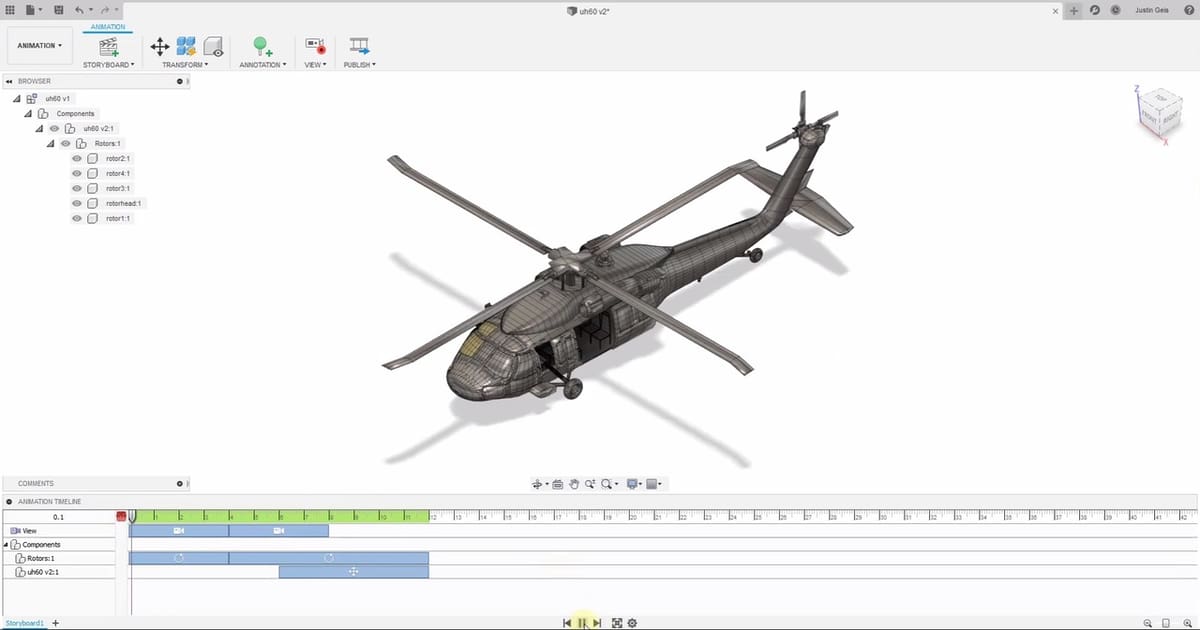

Although there are a plethora of well-thought-out and powerful programs made specifically for 3D animation, 3D animation can also be achieved with the use of CAD software.

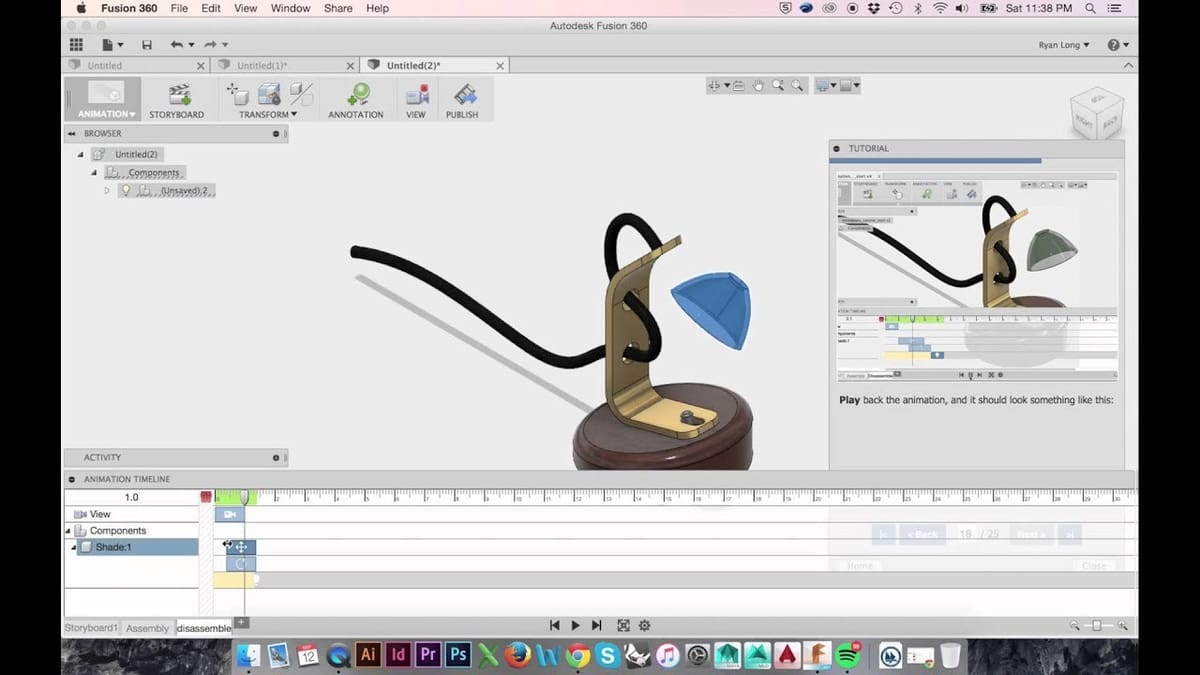

Unlike dedicated animation programs, CAD animation allows designers and makers to create fully fleshed-out 3D designs just as you would in the normal way, and then animate them to show how they work. It’s often as simple as making the separate parts of the model, creating an assembly, checking that all parts are joined, and then finally using the animation tools to make the different parts of the assembly move in the desired fashion. Programs such as Fusion 360 and SolidWorks have dedicated tools within them to enable the animation of mechanical movements or to illustrate a product’s intended human interaction.

Another CAD-based way of approaching 3D animation would be through the use of the popular Blender software. Although Blender isn’t a parametric program and has fewer strengths in precise engineering modeling, its advantages are that it’s free and can produce professional-looking results. It does, however, have a steep learning curve and isn’t as well suited to animating non-organic forms. For this section, we’ll be focusing on parametric CAD programs that have built-in tools.

Fusion 360

Fusion 360 is free for students and hobbyists, so giving this program a go is a must if you’re looking for an entry point into parametric modeling and subsequent animation. With countless video tutorials, its clean, simple, and intuitive UI will make approaching animation less daunting than the alternatives.

Animation in Fusion 360 really is as simple as designing two individual parts, putting them together in an assembly, and then using that assembly in the animation space to make one part move in relation to the other. The timeline is similar to what’s offered in non-CAD-based animation programs, so it should be familiar. Even complex things like moving camera angles, panning, and tilting, are easy. A video tutorial by The Fusion Essentials leaves nothing up to guesswork, illustrating how simple and effective animations in Fusion 360 can be.

SolidWorks

If you’re thinking of investing in SolidWorks, it might be nice to know it’s got a built-in animation tool, similar to the offering within Fusion 360. It is, however, a little less user-friendly, with more steps required to reach similar-quality animations.

Animation in SolidWorks is done in a slightly different way: A timeline is offered, but the most important thing will still be the parts tree, just as it is when making a part. While animation is certainly doable in SolidWorks and can produce impressive and lifelike physical simulations of different materials, it’s not the program’s strong suit.

Applications

So where exactly is 2D, 3D, and CAD animation used? Here are a few common application areas.

2D Animation

- Text and logos (motion graphics)

- Explanatory supplements in educational videos

- Children’s TV

- 3D animation storyboarding and prototyping

- Games

- Animated infographics and advertisements

3D Animation

- 3D motion graphics

- TV shows and movies

- Game cutscenes

CAD Animation

- Demonstration of product ideas in motion

- Assessment of working parts

- Iterative design analysis

Which Is Right for You?

To answer this, think about your goal. Is it to help explain a set of verbal instructions, or is it to promote a product? Are you trying to tell a story, or are you trying to describe how something works?

Additionally, thinking about your target audience is important. As an example, if you want your product promotion animation to be part of a presentation pitch in front of investors, the outcome may be different from presenting to a design consultancy.

In this example, it’s likely that employees at a design consultancy would have a higher degree of knowledge about mechanical components and materials than investors. Because of this, a difference in style would need to be considered as well as which type of program would be best suited:

- Complex, technical animation is better in CAD. Due to the background knowledge held by staff at a design consultancy, they would be able to understand a more complex model or a wireframe view, including cutaway sections and demonstrations of flow and stress. An animation made in a CAD program would be better suited for this purpose, as standard 3D animation software would struggle to convey physics as accurately.

- Simpler, visually-appealing animation is better in 3D animation software. Investors, as business people, most likely wouldn’t have the background knowledge of design and engineering, so a more simplistic approach might be better. This is where a more aesthetic, less detailed animation may be more suitable, created in a 3D animation software with an emphasis on human or organic interaction. A simpler animation, coupled with facts and statistics, may be a better route to go down.

Other examples of a target audience could be defined by age, interest, or level of education or understanding. A very young audience could find 3D aspects harder to follow and may find 2D animations more engaging, for example. 2D animations of mechanisms could also be more appropriate, depending on the specific requirements.

Popular Programs

Having a better idea of where you stand between the worlds of 2D and 3D animation, it’s time for a quick rundown of all the most popular animation programs. Check below to see which one would best suit your needs.

2D

Adobe Animate Creative Cloud (CC)

Free trial, $20.99/mo, $52.99/mo for all CC apps; Windows and Mac

Formerly known as Macromedia Flash, then Adobe Flash, Adobe Animate CC (Animate for short) is a thorough vector animation tool used by many professional animators. It has its strengths in creating animations for online interactivity such as small games, animated buttons and menus, and static animations like banners, GIFs, infographics, and moving logos or text. Utilizing HTML5, WebGL, and SVG file formats, short animated films and TV shows can be made with Animate too, but the workflow isn’t as streamlined as more dedicated programs.

Toon Boom Harmony

$25/mo, $63/mo, and $115/mo; Windows and Mac

Hotly contending with Animate for the top spot, Harmony comes in three different versions at three different price points: Essentials, Advanced, and Premium. With each successive version, more features are included such as bitmap drawing and 3D stage support. This program’s strengths are that it can create longer and narrated 2D animation and has a more feature-rich toolset, though it has a bit of a steep learning curve. Harmony has been designed with the workflow of 2D animation for TV in mind.

Visme

Free with limited functionality, $15/mo, $29/mo; Windows, Mac, and Linux

Visme is a relatively new player in the field of 2D animation software, and is wholly cloud-based, which means you don’t have to worry about system requirements to use it. It’s an all-in-one content creation platform, with a strong emphasis on animated graphics, overlays, ad banners, and infographics. One drawback is that to export a created animation as a moving GIF or video, the $29/month “Business” subscription is required.

Other Options

- OpenToonz (Free; Windows and Mac): If animating is your game, but you think spending money is lame, OpenToonz may be right up your alley. This open-source program has a dedicated subreddit and its simple and intuitive layout means it’s easy to get to grips with. While the software is great for basic animations, it lacks many of the advanced features Animate and Harmony have. That said, it’s an ideal program to have if you’re looking to get into 2D animation as a complete beginner.

- Pencil2D (Free; Windows, Mac, and Linux): Another no-cost offering, Pencil2D may be just what you’re after if you’re looking for an incredibly simple, easy-to-learn program. In many ways, its output is similar to what Macromedia Flash was capable of about fifteen years ago, though some very polished animations have been made using Pencil2D.

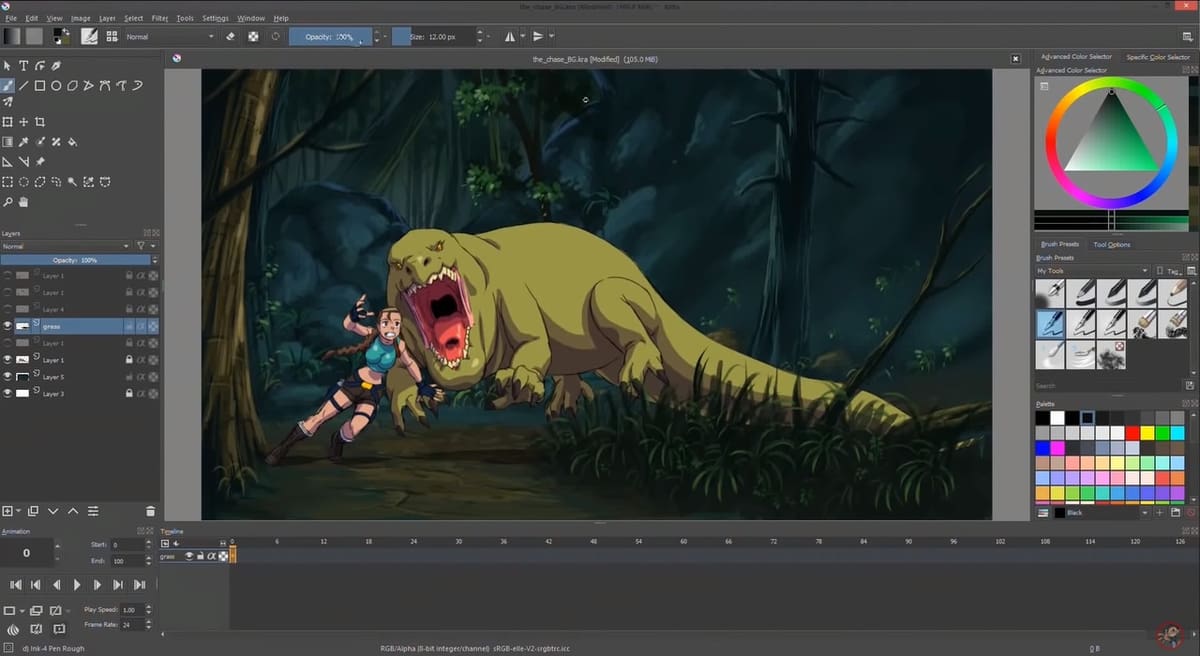

- Krita (Free; Windows, Mac, and Linux): Touted as a professional level 2D drawing program, Krita has recently annexed an animation functionality. Initially added as an afterthought, the animation functionality in Krita has since grown and is already a fleshed out and well-rounded alternative to Animate and OpenToonz. Due to its nature as, first and foremost, a drawing software, it’s possible to create some truly beautiful 2D moving pictures with Krita. For animation, it features useful tools such as onion skinning, animated raster layers, and frame-by-frame editing.

3D

Many programs are at an animator’s disposal to create wonderful 3D animations, but a good starting point would be Blender. With a huge feature set and a broad range of applications and outputs, Blender has the potential to be used for basic 3D animating as well as very complex, professional videos.

Another approach would be Cinema 4D, a highly capable animating program that has realistic light and shadow rendering plus fluid simulation. Cinema 4D is often used to produce true-to-life architectural rendering and walkthroughs, but can also be used for organic 3D animations.

Blender

Free; Windows and Mac

One of the best all-around programs out there, Blender has it all. Its open-source nature, huge community, and broad feature range make it one of the most useful tools available for 3D animation. Blender allows users to sculpt 3D forms within the app and animate them in a step-by-step process. It even has support for 2D animation. It does, however, have a steep learning curve and good results are achieved after a lot of time spent learning the program and experimenting.

Cinema 4D

Free trial, $99.91/mo, $719/yr ; Windows, Mac, and Linux

With the Studio edition, Cinema 4D offers professional-level 3D animation capable of producing short films and even feature-length pieces. Particle and fluid simulation tools, as well as specialized character animation tools, make this a good program if you’re looking for a specific and powerful feature-set. It’s also capable of producing architectural renderings and photorealistic walkthrough simulations. It’s often considered easy to get the hang of, with a clean interface and simple workflows.

3ds Max

Free trial, free for students, $205/mo, $1,620/yr; Windows

This offering from Autodesk is similar to Blender in how 3D forms are produced, but lacks the open-source aspect. That could be considered a blessing, however, as it’s simpler, and the fewer features lend to easier navigation and quicker production of animations. It may lack some of the more advanced tools Blender has, however, limiting production to less complex animations.

CAD (With Integrated Animation Tools)

Coming last but certainly not least in the list is CAD, utilized to animate 3D assemblies. These two examples are distinct from the aforementioned 3D animation programs in that they are primarily designed for parametric engineering. In other words, 3ds Max, for example, is a highly capable 3D design program, though it’s not necessarily intended for manufacture-ready products.

Fusion 360

Free trial, free for students and hobbyists, $60/mo, $495/yr; Windows and Mac

With its dedicated animation workspace, the path to animating your assemblies in Fusion 360 is simple and streamlined. Its intuitive tools mean going from a static model to a fully animated video is quick and easy.

SolidWorks

$1,295/yr; Windows

SolidWorks is a powerhouse of a program so it should come as no surprise that it’s also capable of animation. It’s a little harder to work with compared to Fusion 360, however, as it’s under the elusive “Motion Study” tab. Once there, the interface will take some getting used to, but SolidWorks can produce similar results to Fusion 360 with a bit more time.

A Final Word

With the above in mind, you’ll be able to more appropriately select the right animation for your intended outcome. Whether it’s making tutorial videos or pitching your invention to Google, you’re sure to have a better understanding of how animation works and how to go about creating your perfect piece.

Are you the next Walt Disney? Who knows! Just remember us when you’re raking in your billions!

Lead image source: CAD CAM TUTORIAL via YouTube

License: The text of "2D vs 3D Animation: The Differences" by All3DP is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

CERTAIN CONTENT THAT APPEARS ON THIS SITE COMES FROM AMAZON. THIS CONTENT IS PROVIDED ‘AS IS’ AND IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE OR REMOVAL AT ANY TIME.