The term “open source” is borrowed from software development models in which the source code is open for anyone to review, modify, enhance, and use. It’s an open design method that allows for broad co-creation, and it’s applied today to many kinds of products and initiatives.

An open-source project, for example, simply denotes that the critical files needed for the project – both hardware and software – are made available and freely redistributable. In the hobbyist 3D printing context, fully open-source projects are those that include the public release of CAD design files, custom firmware source code (if any), firmware configuration samples, and a bill of materials. Open access to this information allows users to understand, build, and later modify their machines.

Consumer 3D printing was born out of open-source projects affiliated with the RepRap community, and thanks to their efforts, we can enjoy this technology at very accessible prices. However, things today have become more complex.

While hobbyists and community-based groups still consistently innovate by sharing their ideas and designs, the emergence of commercial 3D printer manufacturers has complicated matters. The industry is wrestling with the need to protect commercial interests while also serving a community very steeped in open-source ideology.

On one end of the spectrum, we see community-based projects that publish fully open-source printer designs, and on the other end, commerical printers that are completely locked down in both hardware and software. But there’s a lot happening in between these two poles. In this article, we’ll explore the full spectrum of open-source 3D printing and why the community is needed to keep it alive.

Let’s dive in!

A Bit of History

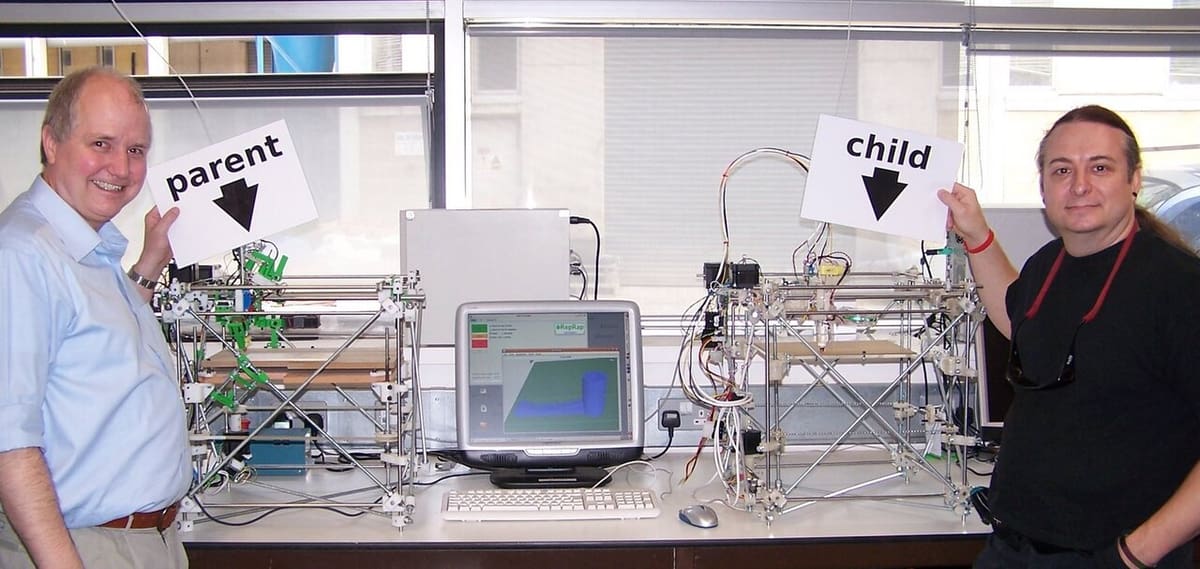

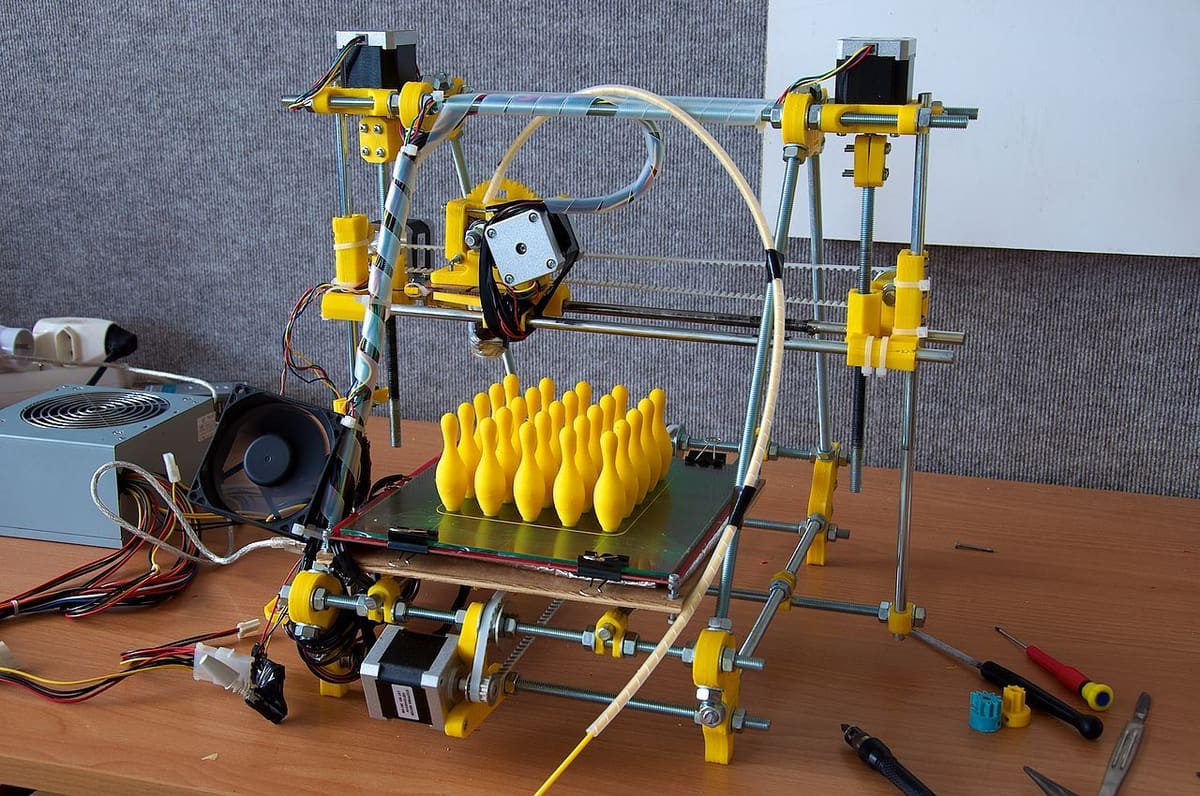

Consumer 3D printing using the fused deposition modeling (FDM) process truly began with projects such as the RepRap (short for “replicating rapid prototyper”) initiative, an effort to design a 3D printer that could replicate most of itself, thus spreading the technology faster. At the time, 3D printers were too expensive and basically inaccessible to the average consumer.

Dr Adrian Bowyer, an English mathematician and engineer, started the RepRap project with the goal of putting affordable machines in the hands of the earliest adopters. How? The idea was simple: 3D printers were used to print many custom parts of themselves. Unprintable parts such as hardware, electronics, and linear motion components could be relatively easily purchased.

In the RepRap days, makers would share and discuss their ideas and projects on community forums, such as the RepRap forums. CAD and firmware files were openly shared either through the RepRap forums or pages like GitHub, allowing users to experiment and collaborate. Because of the open-source nature of the designs, new iterations came swiftly and plentifully, allowing the community to improve FDM 3D printing as a whole.

Fast forward to the present, the consumer FDM market has exploded, and a huge array of machines are commercially available. Looking at how far and fast consumer-grade 3D printing has developed, it’s safe to say that the RepRap initiative was a great success. Some companies even live up to the RepRap ideology by employing massive print farms that produce parts for their own production-grade products.

Regardless of whether you practice or agree with the open-source ideology, we’re indebted to the RepRap pioneers for promoting such a powerful technology to be increasingly used by DIY makers and small businesses.

Benefits

Open-source principles continue to be important within the 3D printing community today, as there are clear benefits to users.

Less Reliance on Manufacturers

Open-source hardware and software allow your machine to remain operational regardless of what happens to the manufacturer and its support. In theory, any broken part can be reproduced once the complete design is open to everyone. For example, you could repair your printer by either using off-the-shelf parts or designing your own fix. This frees users from relying only on the manufacturer for spares, which vary in availability and price.

Upgradability and Customizability

Printer owners are able to design their own modifications based on the specifics of their machines. Improvements can be made to boost their 3D printer’s capabilities according to the user’s needs. Without open-source files, it can be very difficult and tedious to design hardware or software modifications. In many cases, a lot of reverse-engineering would be necessary.

Community-Driven Innovation

Most importantly, open-source principles make the latest technologies and printers more accessible and cheaper for everyone. As more people use and modify currently available technologies, sharing those modifications allow for innovation in the 3D printing community as a whole.

For example, innovations in CoreXY kinematics for FDM printers only exploded in popularity as a result of development and innovation from the Voron community. Lightweight extruders may be common now, but they result from the early (and still popular) Sherpa Mini and Orbiter extruders, both of which largely outperform other extruders at a fraction of their heft. Of course, these are just two examples; there are many more.

Although open-source principles are beneficial to consumers, this may not be the case for companies. The industry has seen the emergence of clone products that are near exact replicas of open-source printers and parts that were initially designed and manufactured by other companies.

Openly releasing all of the details of one’s products comes with the risk of allowing competitors to incorporate one’s innovations easily into their own products – and with a fraction of the R&D costs. This impacts a company’s ability to distinguish its product assortment from others and may potentially lead to the loss of sales and market share. When it comes to community-based open-source projects, these risks are non-existent, as they’re largely free of the pressures that impact businesses.

Consumers and the industry as a whole benefit immensely from open-source principles, but the situation is more ambivalent for commercial enterprises. This begs the question whether the 3D printing community will rally behind and support businesses that are commited to open-source ideals.

The Spectrum

In light of the community’s history as well as the on-going market pressures impacting the commercial wing of the community, what is the state of open source in 3D printing today? As we’ve mentioned throughout the article, it’s a spectrum.

Open Source

On one end, there are fully open-source community-based projects and businesses that offer design files, firmware source code and configuration samples, as well as bills of materials. Community-based projects are composed of interested individuals or design teams who collaborate to develop the machines. Files are typically shared through the project’s GitHub page, and collaboration is mostly done through forums, such as Discord channels.

On the commercial front, there are businesses that develop designs internally, then sell their products while also releasing comprehensive information on them for the community’s use. We also see businesses that manufacture open-source designs – sometimes in collaboration with the original designers – for the convenience of those who do not want to source, produce, and assemble the designs themselves.

Limited

Next, there are some businesses that publicly tout and advocate for open-source ideals; however, they release a limited amount of information to the community. In some cases, full disclosure of information is limited to old, depreciated products. For more current products, critical information such as CAD files or bills of materials are not openly shared.

Often, the firmware is open source due to legal requirements. Firmware packages that are forks of fully open-source firmware, such as Marlin and Klipper, are legally required to be open source due to the GNU General Public License. The same goes for slicing software.

Closed Source

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we have fully closed source. Outside of documentation related to the operation of machines, nothing is shared with the community. Some companies even develop custom 3D printer firmware to avoid the GNU GPL’s legal requirements.

Patented technologies also belong to this side of the spectrum. While this is common among manufacturers of industrial 3D printing technologies, some businesses are moving to patent parts that are frequently used in consumer-grade 3D printers.

Examples

To illustrate better the open-source spectrum in 3D printing today, let’s take a look at some examples.

Voron Design

Created as an independent project to design fun and affordable 3D printers, Voron Design has grown into a large community and is now a well-known name in the 3D printing world. This community has already released five different printer designs as well as other printer components, all which are fully open source. You’ll find on the GitHub pages the following:

- Fully editable CAD design and STL files

- Common and sample firmware configurations

- Comprehensive and well-labelled build manuals, which are constantly improved and updated

The designs are typically initiated and collaboratively developed by passionate community members; some go on to become “official” Voron designs. The majority of the updates and innovations are a result of active discussions on the community forum and Discord.

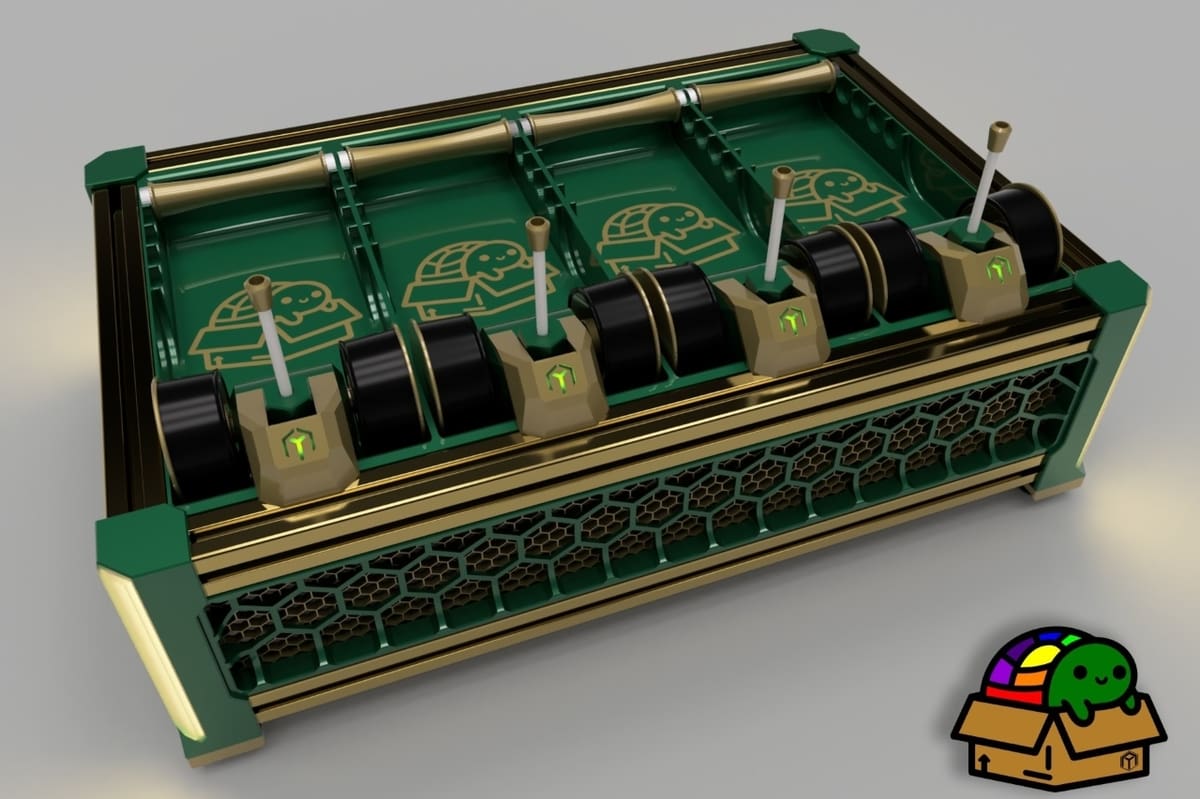

There’s a huge pool of mods and upgrades that have been designed by individuals or small, independent groups. Some examples include the ever-popular magnetic Klicky Probe and the Enraged Rabbit Carrot Feeder, a multimaterial unit.

Voron Design is often regarded as the gold standard of open-source 3D printing, a feat that’s made easier by being a community-based project.

Rat Rig

Rat Rig is a Portuguese company that develops and sells DIY kits and parts for 3D printers and CNC machines. Much of the development of both hardware and software is done in house, and the company enlists its user community to participate in beta testing.

Despite being a commercial enterprise, open-source principles are alive and well at Rat Rig. Driven by the motto “Your Rig, Your Rules”, the company provides fully open designs to facilitate the use and adaptation of their machines by users. For example, the V-Core 4 3D printer was released in 2024, along with CAD models, STL files, a bill of materials, a build guide, and other documentation. The design iteself is licensed under a non-commercial Creative Commons license that permits sharing and remixing with proper attribution.

Even pre-release or unreleased designs are made available. Thanks to the openness of their work, a large community has developed around Rat Rig machines. It’s possible to find community-designed mods and upgrades on all of the popular 3D printing related model repositories.

Rat Rig is a evidence that it’s possible to run a commercial 3D printing enterprise without sacrificing open-source ideals.

Prusa Research

Prusa Research grew out of Josef Prusa’s involvement in the RepRap community. In October 2010, he shared a simplified remix of the Mendel, one of the early RepRap printers. Within five years, Prusa Research was founded and the Original Prusa i3 hit the market. With such deep roots in the community, the company reports holding open-source principles in high esteem, even as the company has come under fire for paring back what they openly share.

At the heart of the Prusa Research’s approach to open-source ideals is the desire for their printers to “remain moddable, easily repairable, and produce amazing prints even decades after their initial release.” Accordingly, files for printable parts, the firmware source code, electronic schematics, and information on other hardware features are accessible either on their open-source page or in the user manuals. The company has also committed to keeping PrusaSlicer open source – which is, in part, related to Slic3r’s AGPL license (PrusaSlicer is a heavily modified fork of Slic3r).

A very vocal contingent within the community, however, takes issue with the delayed release of information for newer printer models – a move the company has made to protect against companies that, in Josef Prusa’s phrasing, aren’t playing by the same rules. Electronic schematics and hardware manufacturing information for new products will not be immediately available. Except for the Prusa Mini, bills of materials are not provided.

Despite the availability of information for the older models, some question the quality of the information provided. For example, the electronic schematics are not updated regularly and may not reflect the actual shipped product. The GitHub for the MK3+ electronics includes the following caveat: “There is no (warranty) for these files in any way. There may have been some undocumented tweaks by various designers, engineers, manufacturers, suppliers, and assemblers to make this a functional product.”

The company frames these protectionist measures as a response to “1:1 clones of hardware or software… that do not bring anything back to the community.” This is an oft quoted passage among reactions to Prusa’s blog post on the state of open source in 3D printing, with many arguing that changes to open-source licensing will do nothing to stop copycats. Rather, continued innovation and keeping pace with shifts in consumer demographics will allow Prusa Research to maintain a leadership position in the industry. Some point to stagnation during the MK3 days, and once the MK4 finally dropped, even we found the printer not the most innovative compared to the competition.

Access is another significant point raised in the discussion of clones. Users who value and can afford a premium machine are likely to buy a Prusa printer. The steep price, however, is a barrier for those of us with more modest pocketbooks. Beyond price, many cite product availability, delivery lead times, and shipping costs as hurdles that drive customers to clone manufacturers.

The community, however, is not a monolith. There are many who revile Prusa Research’s decision to limit what it shares, and there are many who praise the company’s actions to protect itself from bad actors in the industry. From a purist standpoint, Prusa Research is no longer fully open source as we see with community-based projects. That being said, the company is still doing more to support open-source ideals than other prominent printer manufacturers.

Creality

Creality has a mixed reputation when it comes to open-source principles. Thanks to community pressure and the influence of Shenzhen-based engineer and maker Naomi Wu, there was a flurry of open-source activity at Creality from 2018 through the early 2020s. In June 2018, the Ender 3 became the first Chinese 3D printer to be certified by the Open-Source Hardware Association (OSHWA). The CR-10 followed suit in early 2019. All documentation – including CAD files, bills of materials, firmware, among others – can be found on their respective GitHub pages (Ender 3 and CR-10).

Wu even spearheaded a belt 3D printer project (3DPrintMill / CR-30) at Creality, wrangling from the company’s leadership a commitment to open source the project if $5 million could be crowdfunded to offset the R&D costs. The Kickstarter campaign was praised by some for its open acknowledgement of the RepRap movement, the Open Source Marlin Project, and other makers whose innovations informed the CR-30 project. Unfortunately, the campaign fell short of the target, and today, only the firmware is openly available.

Since then, it seems open-source principles have fallen on hard times at Creality. The original Ender 3 has been overshadowed by newer models. The Ender 3 V3 SE, for example, offers auto-bed-levelling and high-speed printing, among other improvements, for almost the same price point. While Creality released the Marlin-based source code for the Ender 3 S1 and S1 Pro, none of the newer models are fully open source. The same is true for the CR-10. It was superceded by closed-source models like the CR-10S, CR-10S Pro V2, and the CR-10 S5.

In 2023, we called out Creality for its unethical implementation of open-source Klipper firmware in the K1. The printer launched with Creality OS, which in our testing, appeared to be a version of Klipper that had been gutted of user-friendly features. The community uproar over Creality’s potential violation of Klipper’s GNU GPLv3 pushed the company to release their source code for the K1.

The release of firmware and software derived from GNU GPL-licensed sources, however, falls short of the open-source ideals that gave birth to consumer 3D printing. Naomi Wu’s 3DPrintMill project with Creality is instructive: Large manufacturers are concerned about recouping the costs to bring new printers to market, and for some, open-source principles are seen as a threat to the bottom line.

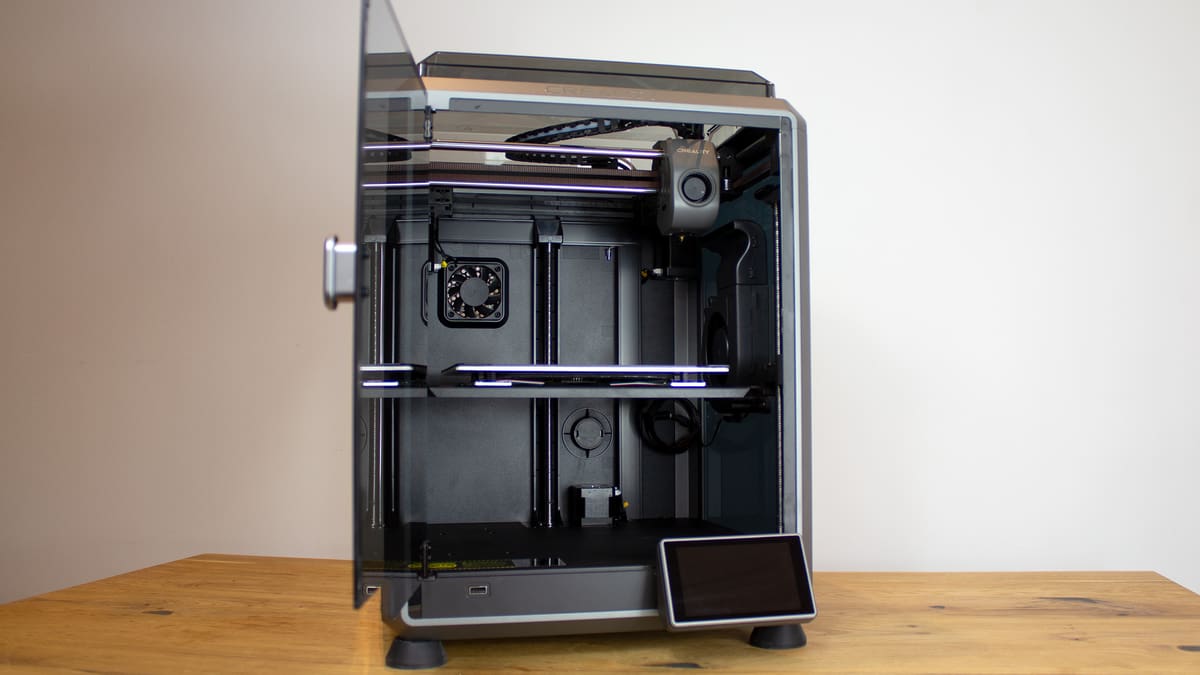

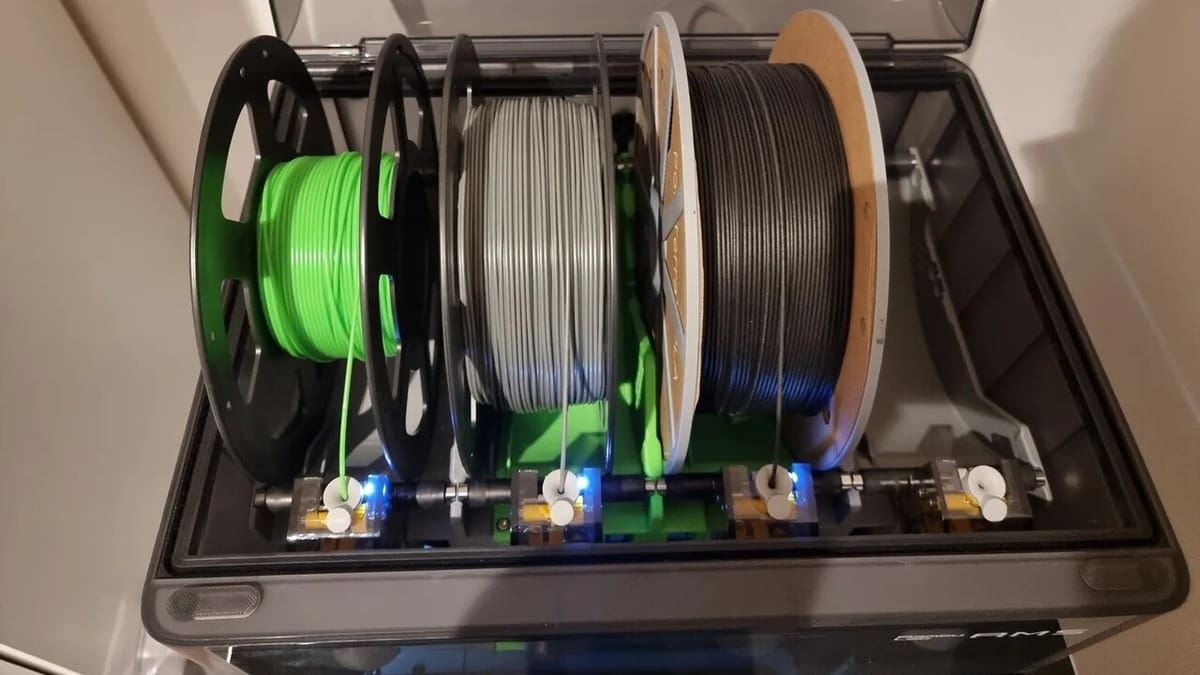

Bambu Lab

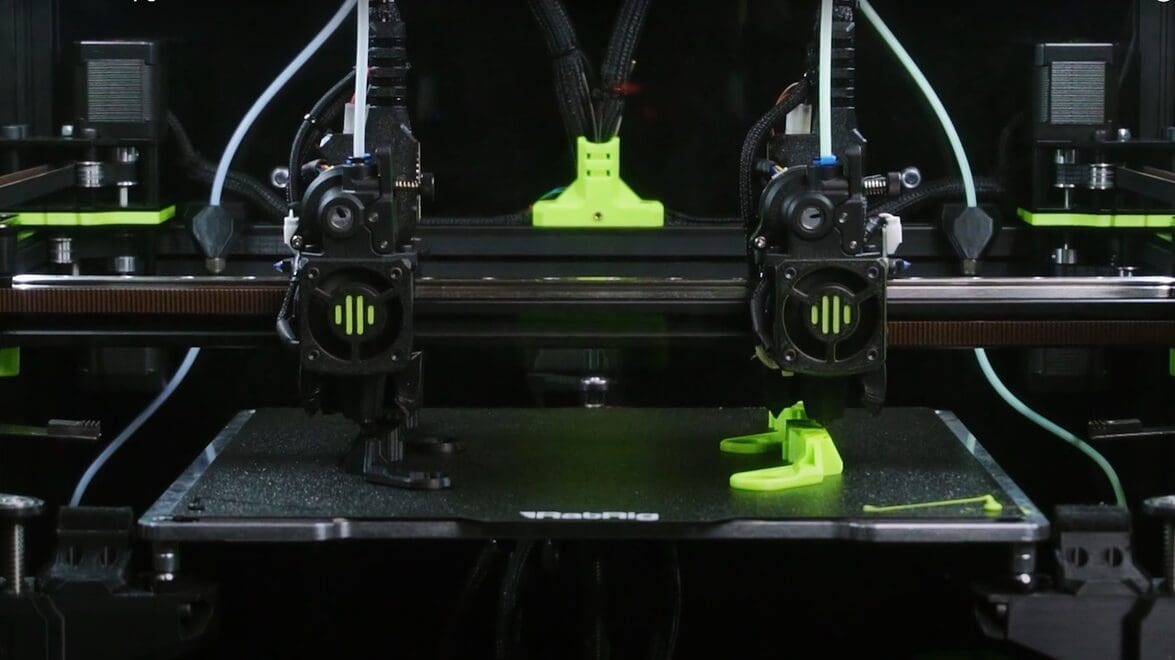

Bambu Lab has released high performing CoreXY 3D printers at a lower price point than current commercially available machines, enabling users to come close to the performance of DIY-built printers. Unsurprisingly, their printers borrow many innovations from community projects, as seen from relatively similar design choices. In fact, the company has acknowledged consulting these projects during their R&D.

Despite the company’s awareness of and indebtedness to open-source principles within the 3D printing community, Bambu Lab machines are largely closed systems when it comes to hardware and firmware. Their slicing software Bambu Studio is open-source – a legal requirement, as it’s based on open-source software.

In a blog post from 2022 on whether or not to open source their products, the company frames the decision to keep their products proprietary as retaining competitive advantage. They write, “we do have 100+ employees, and this number is growing. We want to make our business successful so that we can provide for each of our employees.” However, they do dangle the possibility of open-sourcing everthing to everyone in the event the company goes under.

Regardless of Bambu Lab’s closed ecosystem, the community continues to do what it does best: innovate. A number of community-developed open-source modifications are gaining traction among Bambu Lab users. For example, the Hydra AMS is a further improvement of Bambu Lab’s existing AMS system. In early 2024, news broke of non-official, community-developed firmware that jailbreaks the X1 and allows it to run the X1Plus firmware.

While the company relented on the issue of third-party firmware, Bambu Lab has once again drawn the ire of the community, thanks to plans to remove third-party hardware and software’s access to their machines. The initial plan included a firmware update that would bring a new authorization system and also disable its network plug-in API for third-party software, preventing 3D printer control from such applications. As many use third-party tools with their Bambu Lab printers, this didn’t sit well at all with the community as well as business users. In response to the pressure, the company has since modified their plans for the firmware update.

In spite of the decision to close source its product line, it would be unfair to represent Bambu Lab as tone deaf to the open-source principles underlying the 3D printing community. They openly acknowledge benefitting from the community and have expressed a desire to “give all our knowledge back to the community”. They have been responsive to feedback and users’ desire for more open access to Bambu Lab machines. Further, they’ve committed to investing licensing income from their deal with E3D back into community in the form of donations to the Sanjay Mortimer Foundation and the establishment of a foundation that supports emerging 3D printing talent and small businesses.

Nevertheless, it’s still up to the community to continue applying pressure on Bambu Lab and all commercial 3D printer manufacturers to ensure the machines we buy and own can be freely used and adapted as suits our needs, not the manufacturers.

License: The text of "Open-Source 3D Printing Needs You to Survive" by All3DP is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.