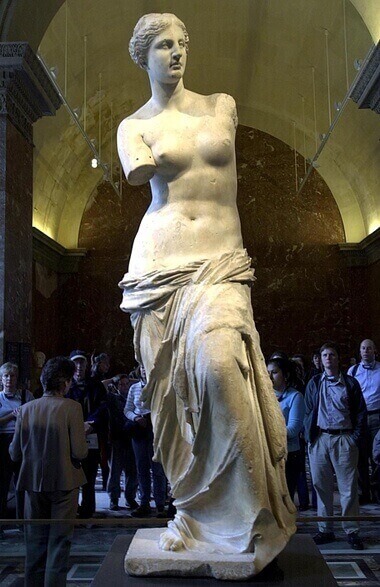

For centuries, archeologists were looking for an answer to the question: who was the Venus de Milo? Thanks to 3D printing, we now have a new, interesting theory.

People say that part of the beauty of the Venus de Milo sculpture is the mystery of the missing limbs. But archeologists don’t buy it: they want to know what her arms were doing so that they can situate the sculpture better within its original context. Now, with 3D printing, so-called experimental archeologists are using rapid print production to test their hypothesis.

A collaboration between open-access 3D printing advocate Cosmo Wenman and writer Virginia Postrel has helped experimental archeologists crack the secret of the missing limbs. Knowing what Venus is doing with those arms doesn’t only completes the artwork, but gives researchers more information about the original function and meaning of this artwork.

Venus de Milo Spinning Thread

by CosmoWenman

What Was She Holding? A Shield? An Apple? A Baby?

You might not know that the question of Venus de Milo’s missing arms is the subject of a long historical debate, which Virginia Postrel charts in Slate. Was she holding a shield, ready for war? Was she holding an apple? A baby? These debates about the sculpture’s original context and the history of getting this iconic sculpture into the Louvre in the 19th century are even the subject of a book, Disarmed. A lot of these debates, as you can imagine, become quite specialized: between Classical philogists and textile archeologists, museum curators and French naval officers.

And that’s where Virginia Postrel comes in. Postrel is a writer and cultural critic who read one of these specialized books, from textile archeologist Elizabeth Barber, a professor emerita from Occidental College in California. Tucked inside a pretty long scholarly book is a picture of the Venus de Milo with both arms, holding a spindle and spinning wool into thread. For Postrel, a lightbulb went off.

She teamed up with Cosmo Wenman, an activist bent on encouraging museums to produce and release 3D scans of their sculptures for public access. He’s used software like Autodesk123D Catch to stitch together his hundreds of photographs of sculptures to create 3D printable models: like the Getty kouros, a famous sculpture of a young man at the Getty museum. The Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. and the Metropolian Museum of Art in New York City are already leading the way in this technology…and Wenman and his partnership with Makerbot is driving this.

The IP law surrounding this work is, undoubtedly, complex—and the commercial applications of these digitalized artworks do give one pause. But Wenman’s passion is contagious. Postrel and Wenman worked to plan and print a 3D version of Barber’s illustration. Wenman had already scanned a plaster cast of the sculpture at the University of Basel (get your own here!). Maybe, as Wenman suggests, 3D scanning these sculptures is the modern equivalent of creating a plaster cast model used in the 19th century!

So: What Did They Learn?

The Venus de Milo could definitely have been spinning thread. So what? Why would a goddess be spinning thread at all? Here’s where a little history comes in handy. Let’s remember that these sculptures before industrial textile manufacturing, and all thread was spun by hand on a spindle. And “respectable women” weren’t supposed to engage in manual labor, so most women represented spinning wool are also representing doing other things available to them to make money—like prostitution. There are hundreds of representations of prosistutes spinning wool while waiting for their next client—maybe even to entice him with their femininity (who knows?)

So then the Venus de Milo, one of the most famous sculptures in the world, is of a prostitute? It’s impossible to know. But 3D printing has shown us that it’s feasible– and expanded the horizons for experimental archeology!

License: The text of "3D Printing May Have Solved The Mystery of Venus de Milo" by All3DP is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.