Researchers from MIT may have just paved the way for using cellulose — the world’s most abundantly available natural polymer — in 3D printing.

Cellulose – to those who haven’t attended a school biology lesson in some time — is the world’s most abundant organic polymer. It can be found in pretty much all green plant life on the planet, and could be a key component of 3D printing materials in the near future.

Research conducted at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology sheds light onto a new method of using this readily available commodity. A boon, when it could mean we get a renewable, biodegradable alternative to the petroleum-based polymers used to create 3D printing materials such as ABS.

MIT postdoc Sebastian Pattinson led this round of research into 3D printing with the polymer. Associate professor of mechanical engineering, A. Jon Hart co-authored the paper published in the Advanced Materials Technologies journal.

To Pattinson, the polymer is “the most important component in giving wood its mechanical properties. And because it’s so inexpensive, it’s biorenewable, biodegradable, and also very chemically versatile, it’s used in a lot of products.”

Cellulose and 3D Printing

3D printing using cellulose is nothing new. Teams have attempted it in various forms in the past with mixed success. One notable example comes from Harvard, and its Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. They co-pioneered a “4D print“ that alters shape when exposed to water.

However, common problems have plagued cellulose’s use in standard printing practice. Mostly due to the organic material’s chemical composition. The polymer decomposes when heated — as you need to 3D print it — rendering it unusable before the material reaches the requires flow to print.

Similarly problematic, intermolecular bonding in high-concentration solutions result in a material too viscous to use effectively.

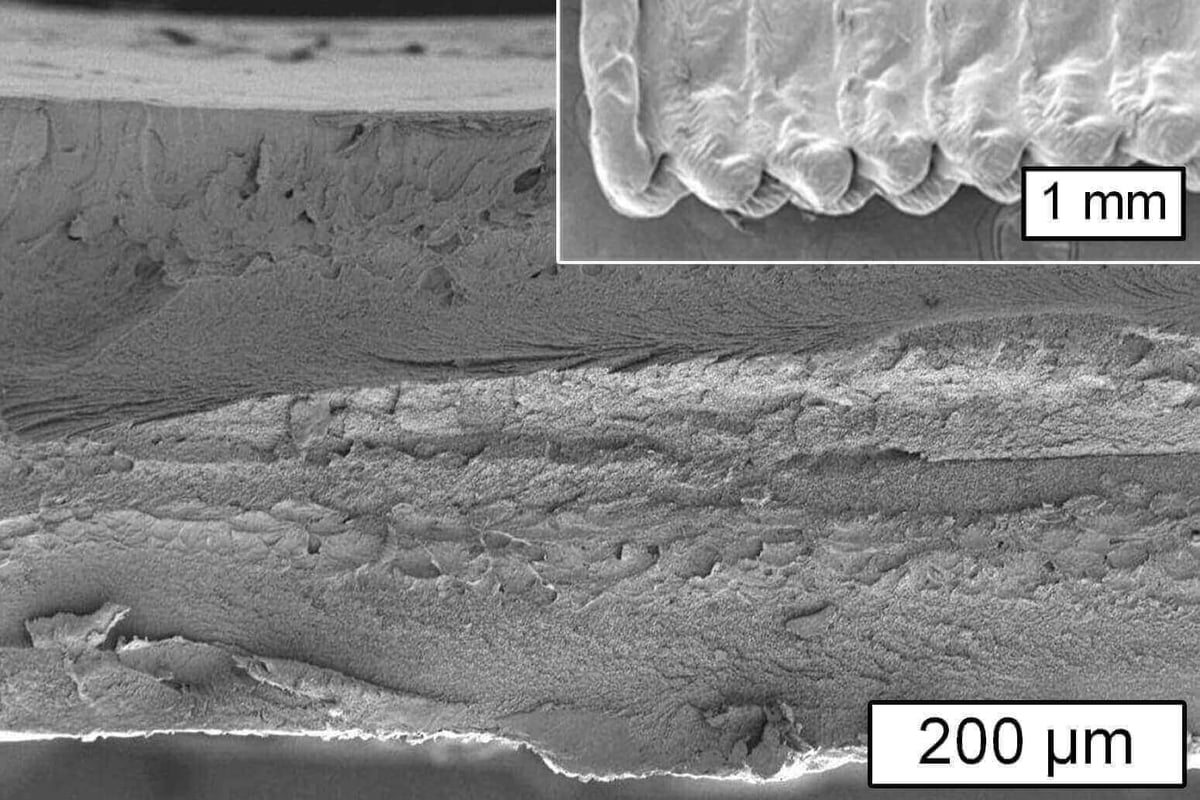

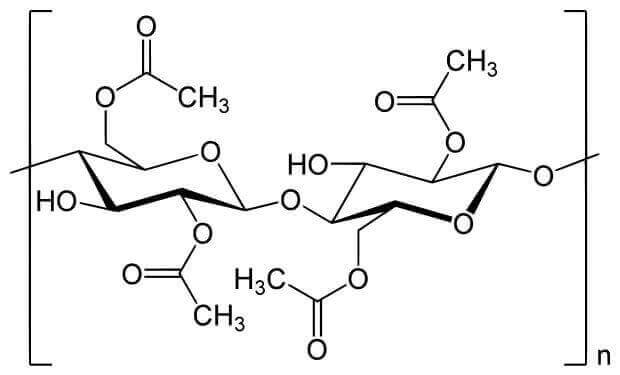

To get around known issues with the biopolymer, Pattinson and team use cellulose acetate instead.

You have encountered this material before. It appears everywhere, from the likes of cigarette butts — as a synthetic fiber — and sunglasses frames, to the base of photographic film.

This readily available material features fewer hydrogen bonds — the cause for much of cellulose’s known problems when 3d printing. And, when dissolved in acetone in preparation for printing, the cellulose acetate extrudes and solidifies at room temperatures.

The team’s findings also include that a secondary treatment using sodium hydroxide restores chemical bonds in the print, increasing the strength. Pattinson claims “the strength and toughness of the parts we get … are greater than many commonly used materials”.

Source: MIT News

License: The text of "3D Printing With Cheap Bio-Polymer Cellulose One Step Closer" by All3DP is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.