You’ll be seeing more 100-year-old Harley-Davidson and Indian motorcycles on the road thanks to Competition Distributing, a Pennsylvania-based garage making vintage motorcycle parts more attainable with metal 3D printing.

The company, founded in 1969, which recreates (and improves upon) impossible-to-find motorcycle spare parts, started 3D printing them in aluminum, titanium, and stainless steel just last year and already has a line of custom 3D printed parts for sale.

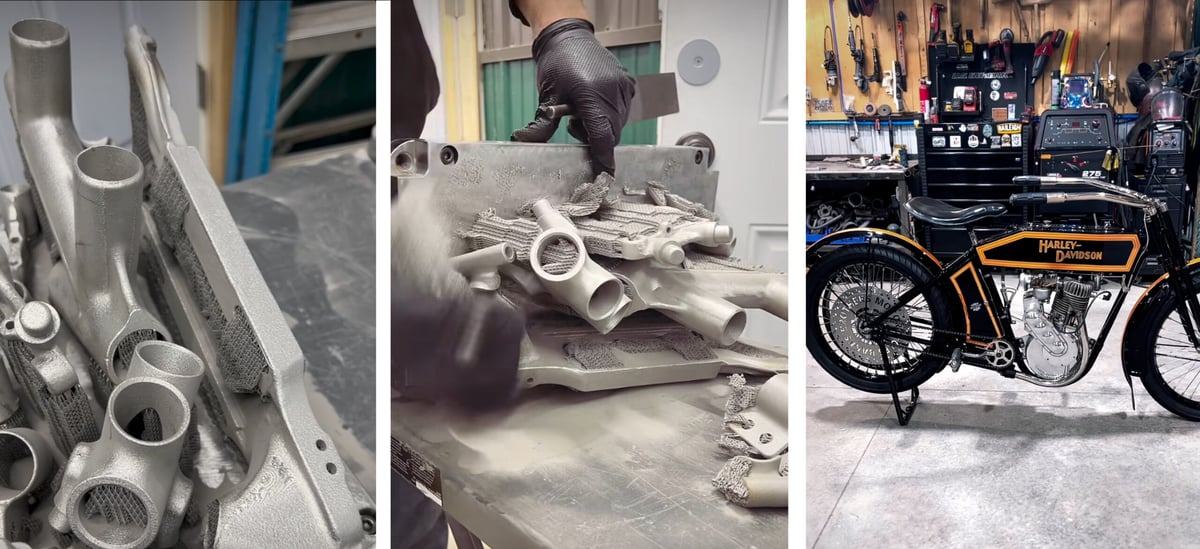

Competition Distributing, which once cast rare parts at a foundry, now 3D prints them, “faster and better,” says company co-owner Sean Jackson, using a Farsoon laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) machine installed in-house.

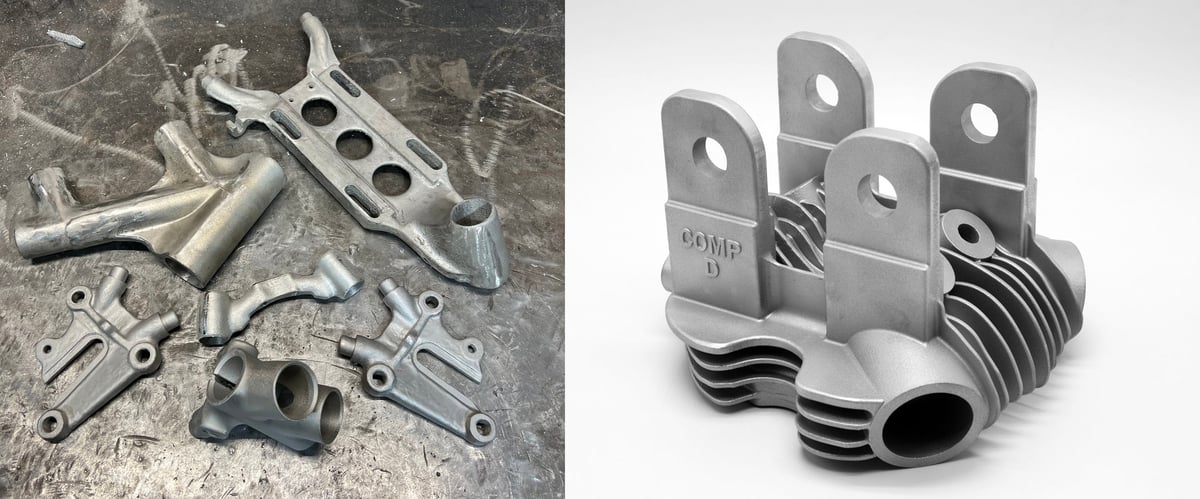

The company 3D prints chassis, cylinder heads, engine parts, connector rods, complete engine cases, and more to repair and recreate vintage bikes. “Additive manufacturing revolutionized the way we create antique motorcycle parts,” says Jackson.

Bringing Century-old Motorcycles Back to Life with Cutting-Edge Tech

“Until recently, we would do things the old-school way,” says Jackson. “We’d make a pattern of an original part, then take that to a foundry and then wait for long lead times.” Once the part was cast, it still wasn’t finished. Cast parts require in-house machining and more steps to get a final usable part, which would often be one of several required to refurbish an antique bike, extending project time exponentially.

“So we decided to invest heavily in additive manufacturing,” says Jackson. And by heavily, he means into a FS200M-2 metal laser powder bed fusion 3D printer and accessory equipment by 3D printer manufacturer Farsoon at a price tag well into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The investment is paying off. Jackson says 3D printed parts are more affordable for Competition Distributing to produce so more accessible for its customers to buy. Overall, a strategic investment once thought to be out of reach for a small company, is proving its worth across multiple projects, enabling new products and new markets.

“If you’re doing low volume, it makes zero sense [to do investment casting] especially for really old parts that you’re not going to sell a ton of because it takes $20,000 to $30,000 in machining just to make the investment cast, so [3D printing] makes it way more obtainable for everybody.”

To recreate vintage components accurately, Jackson uses a 3D scanner with 0.02 mm of accuracy to create a digital file. From there, the file is converted into a 3D digital model and “thrown on the printer,” he says.

“The 3D scanning of original parts can pick up every detail, including numbers, divots, and other uniquenesses,” says Jackson, which can be kept or removed for the final part.

In addition to the true recreation of vintage parts, Competition Distributing improves upon them as well.

“For the Born Free Competition we decided to build our own version of an overhead eight-valve board track racer,” says Jackson. “We developed the entire top end for that engine based on a late ’20s Rudge British racing bike single cylinder originally made out of cast iron. We took that design and made improvements to its port geometry. We increased the intake port size and the exhaust port and made the transition and flow better. Then we printed those heads in aluminum instead of cast iron, making weight and heat dissipation much better.”

Competition Distributing offers a full line of custom cylinder heads 3D printed in titanium, aluminum, or stainless steel.

“People ask me, ‘Is this as strong as a casting?’ and I say these prints are actually stronger than a typical casting, two to three times stronger, to be exact,” says Jackson.

He favors 3D printing quality over casting because, he says, there are no voids or imperfections anywhere throughout the part, like you could have with a casting, where you could have air pockets or places where the molten metal didn’t get into your mold or your pattern.

“When you’re [3D printing] layer by layer in 60-micron layer height, this part comes out 99.8% dense,” says Jackson. “Depending on the material, you could do post-process heat treatment, but we don’t really have to do stress relief on these parts, unless it’s for a cylinder. Once these parts cool, we snap off the support materials, grind-clean the support stops, throw them in the blaster, and then they’re ready to go.”

The company’s Farsoon 3D printer has a 425 x 230 x 300 mm build volume, two 500-watt fiber lasers, and can print every piece necessary for a Harley-Davidson JD model bike frame in one 55-hour print run.

With one 3D printer, Competition Distributing can fulfill its orders for custom and restored motorcycles replicating hard-to-find components for early Harleys, Indians, Hendersons, and more. The technology enables it to create stronger, lighter parts while preserving the original aesthetics or the vehicles.

Follow Jackson’s progress adopting additive manufacturing into his business through his YouTube channel.

License: The text of "Inside the Garage Resurrecting Vintage Motorcycles with Metal 3D Printing" by All3DP Pro is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.