Print the Legend turns 10 years old this year. Debuted at the South by Southwest festival in March 2014 to accolades and acquired by Netflix soon after, the feature-length documentary began streaming on the platform in September of the same year.

Over its 99-minute runtime, Print the Legend charts the rise of some of desktop 3D printing’s early leading companies and personalities, including MakerBot and its co-founder and figurehead Bre Pettis, plus Formlabs and its co-founder Maxim Lobovsky, all set against the backdrop of desktop 3D printing’s early media hype bubble. Bubbles burst, of course, and while we’re not at the then-prophesized point of a 3D printer in every home – we are at a point where the promise behind the claim is real, with several companies achieving a simplicity that approaches appliance-like ease-of-use.

Ten years can be a long time in tech, and while the fundamental technology we see in the documentary is largely the same, a lot has happened since we left off with MakerBot selling (and to some, selling out) to Stratasys and Formlabs’ rocky launch with the Kickstarter-funded Form 1, which was promptly litigated by industry giant 3D Systems, then headed by Avi Reichental, before settlement later in 2014.

Indeed, at the time, 3D Systems, several decades old and an industry leader in additive manufacturing, was ahead of the curve with its Cube desktop 3D printer available in big-box stores. Reichental tells All3DP “From the very beginning, I believed in democratizing access to industrial strength AM and that the sure way to achieve adoption at scale is through affordable desktop units. That is why I developed the Cube back in the day, and that is why at Nexa3D [Reichental’s current company], I developed the XiP. The path to accelerated adoption is through democratized access, and that means speed, simplicity, and lower cost of ownership.”

Cutting throughout the documentary is outsider commentary from disgraced “crypto-anarchist” Cody Wilson, designer of the Liberator 3D printed handgun, whose media-savviness drew mainstream attention to 3D printers’ potential for the production of untraceable firearms and the constitutional wrangling therein.

The documentary is essential viewing for anyone with even a passing interest in 3D printing, following the animated Pettis, co-founder and, for a spell, face, of MakerBot as the company gained fame in the mainstream with front-cover features on newsstand publications including Wired magazine (This Machine Will Change the World), and then shed its maker-friendly open-source origins for closed source and a pivot to education. Similarly, a parallel track is observed with then-MIT student Lobovsky wanting to cut through the fussiness of DIY 3D printing solutions with a sleek one-button box, which would later launch via Kickstarter as the Formlabs Form 1.

The fate of both these companies now is, of course, history, with MakerBot enduring onwards through its acquisition by industry giant Stratasys and eventual merger with Ultimaker to become UltiMaker, and Formlabs’ march to Unicorn status and an independent international footprint. Pettis left MakerBot and would later buy compact desktop CNC manufacturer Other Machine, which later became Bantam Tools. Lobovsky is still CEO at Formlabs, while Reichental remains strongly active in additive manufacturing; since going on to found venture capital firm XponentialWorks, and more recently Nexa3D which makes fast printers for professional users and industry.

A Greater Reach

There’s no denying the US-centric orbit that Print the Legend tracks, but suppose for a second that the show’s regional focus loosened and its timeline stretched.

It seems obvious that figures such as Adrian Bowyer would play some role as a European surrogate, igniting RepRap – the very project to inspire MakerBot – while a senior lecturer in mechanical engineering at the University of Bath, UK. This concept of a rapid self-replicating robot is at the very root of contemporary desktop 3D printing and remains very much alive today with contemporary designs (if not in alignment, certainly in spirit) using completely 3D printed frames and ultra-minimal bills of materials.

MakerBot’s and Formlabs’ hardware were a draw to hackers, tinkerers, and curious consumers alike. Lobovsky’s aim with the Form 1 was to appeal to those disinterested in the fussiness of building their own printer or shelling out tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars for high-quality parts. Over the years since the Form 1, that aim has bore out. “The market has grown in both directions. There are way more hobbyists and tinkerers using 3D printers than there were 10 years ago, but there is also a huge number of people who want to ‘just press print’ and get industrial-grade parts” explains Lobovsky. “Now people better understand that affordable 3D printers can also produce industrial parts, so the number of professionals looking for reliable, professional 3D printers that cost a fraction of $100,000 is bigger than I ever imagined.”

Across the Atlantic from Massachusetts in landlocked Czechia, Europe, a giant of desktop 3D printing was taking its first steps, too. What began as a personal effort to produce custom components for DJ equipment for Josef Průša started a ball rolling toward now-commercially commonplace components and designs in 3D printers of all price points.

“I just did what I loved,” says Průša. “Me and my brother tinkered with 3D printers all day and tried to make them better, and the hobby slowly turned into a small family business. Initially it wasn’t even my intention to sell the printers, but people within the community kept asking for pre-made kits of my version of the RepRap Mendel.”

The contrast between Prusa Research in 2014 and 2024 is stark. “In 2014, we had literally one employee (Hanka is still with us today!), and our 3D printing farm consisted of about 10 printers. The biggest challenge [then]? I guess finding new space for the company… in April 2014, we moved to a nearby flat. So we had our first proper office.” Prusa Research in 2024 is of an order of magnitude greater, “nearing the magical 1000 employee number.”

In desktop 3D printing, the Průša name is synonymous with open-source desktop 3D printing, the color orange, and the inclusion of Haribo gummy bears to coax users through the educational experience of building a printer. It is no stretch of the imagination to picture Prusa Research’s bustling print farm as a backdrop for our imaginary 2024 edition of the doc. A singular focus on product iteration led to innovations such as the PCB heated print bed. The tooling and testing rigs are all custom, as seems nearly everything the company does.

Such has been the company’s trajectory and self-documentation that it even put out its own short documentary: The Road to 100,000 Original Prusa 3D Printers. “If I may be so bold, I think it’s at least as good as the Netflix show” says Průša. “Maybe less dramatic, but it shows everything from our humble beginnings to becoming the largest Western manufacturer of desktop 3D printers.”

The Patent Plot

A challenge Průša faces today and has publicly spoken about is the grapple between innovation, the open sourcing of work, fair usage of that work, and patents holding the space back. Throughout the company’s history, Prusa Research has worn this kind of democratized development on its sleeve but is proceeding increasingly cautiously with its latest products before making them fully open to the scrutiny of public use.

A key plot thread through Print the Legend is of Formlabs’ run-in with 3D Systems and the latter’s claim against unlicensed use of IP – legal action that resulted in a settlement. Despite being the one prosecuting the claim, futurist Reichental laments the framework in place for defending intellectual property and its need to change.

Today, that viewpoint has not changed: “Nothing constrains industries more than antiquated IP laws. Yes, entrepreneurs and inventors deserve protection for a period of time, but in an age in which the average shelf life of a business model is 15 years, down from 60+ years in the mid-’60s, 20-year protection is a lifetime and stifles healthy collaboration and completions at the expense of the customer.”

For Lobovsky, the process was a painful one. “It made everything we did back then – get customers, employees, and investors to trust us – much more difficult. I guess it was instructive because it gave some insight into what the ‘big’ companies in our industry were like and some more motivation to disrupt them.”

Though the discussion of patents and licensing of its innovations have been public talking points, they’re not Průša’s biggest challenge. “Although I am concerned about the future (from thousands of patents blocking development paths to us being kinda left alone as the last man standing in the West), our biggest problem is still manufacturing capacity. Everything we make is desperately sold out, and that’s a good problem to have. We’ll continue to do things our way, as I believe people still value things like reliability and repairability, and not just the absolutely lowest price possible.”

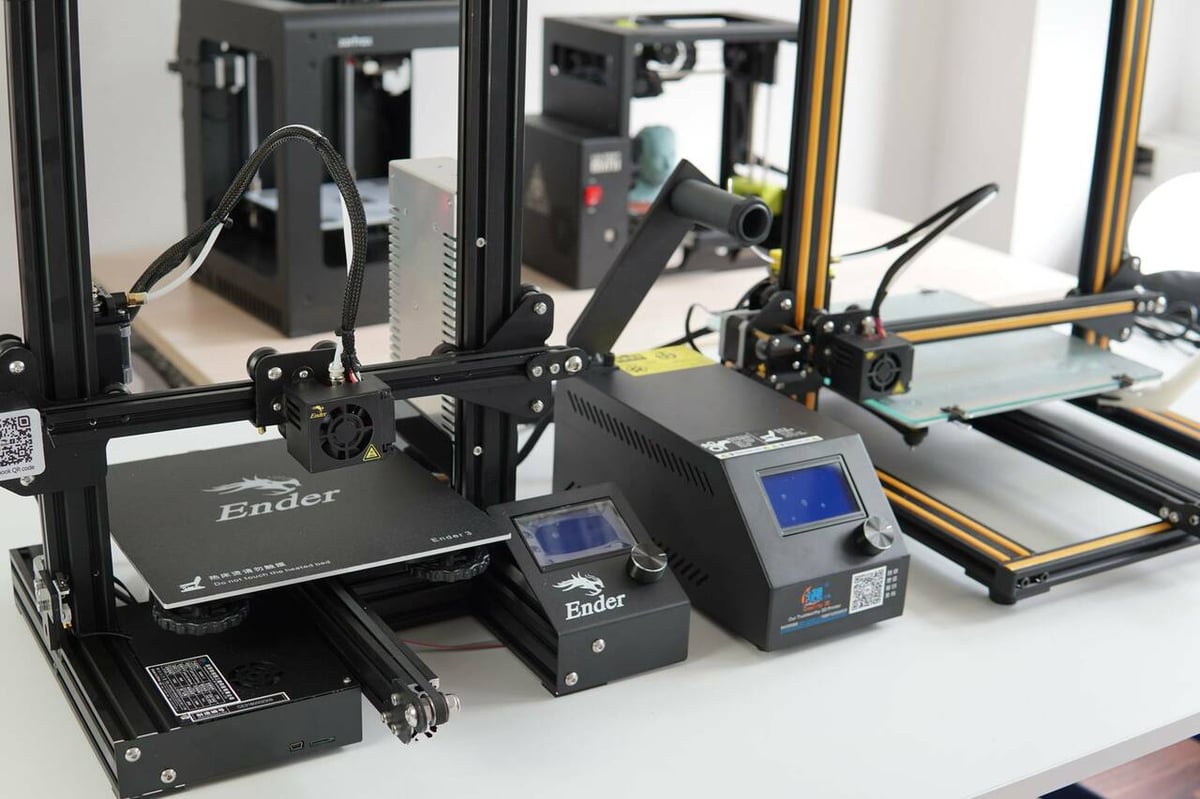

Another keystone that we think should get its share of attention is that of Creality, its manufacturing might as a company operating in China’s tech hub, Shenzhen, and cracking the class of budget 3D printer with the CR-10 and, later, the Ender 3, both serving as a decent starting point for the scores interested in 3D printing, but not necessarily technically skilled or invested in building one entirely from scratch. If RepRap provided the spark for desktop 3D printing, then Creality’s commodification of the tech absolutely threw armfuls of kindling onto the pyre. To date, the company “stands head and shoulders above other vendors” for market share in desktop 3D printing, according to a recent report by Context.

Modern Problems, Modern Solutions

Perhaps instead of Wilson’s narrative and exploring the notion of every 3D printer owner being in possession of a gun-making tool, today’s version of the documentary would focus instead on those same folks having the capability to produce personal protective equipment, as evidenced by the rapid, distributed and communal response to the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic.

As healthcare systems buckled under unprecedented pressure and supply chains dissolved in the face of the impossible demand for PPE and other essential components of the medical supply chain, suddenly, businesses and individuals worldwide found themselves in possession of part of the solution for fast and local production. Many individuals and companies wore their compassion on their sleeves, coordinating face-shield production and distribution, not to mention fast-tracking the creation and certification of nasal swabs for mass testing.

Our coverage at the time tracked several of these initiatives, including OpShieldsUp by Alan Puccinelli of R3pkord and Prusa Research’s Prusa Protective Face Shield, plus parallel nasal swab development and testing by Carbon and Formlabs, to name but a few. It’s a long list, but by no stretch exhaustive, which goes to show the sheer size of the response.

It’s a success story of desktop 3D printing. One that builds on years of efforts to aid society, often in the same open-source spirit that desktop 3D printing as we know it emerged. Efforts like e-NABLE, a distributed, open-source project that facilitates free prosthetics where they’re needed most, and Ayúdame3D, a similar program that leverages personal 3D printer users to aid its fundraising and the printing of prosthetic components.

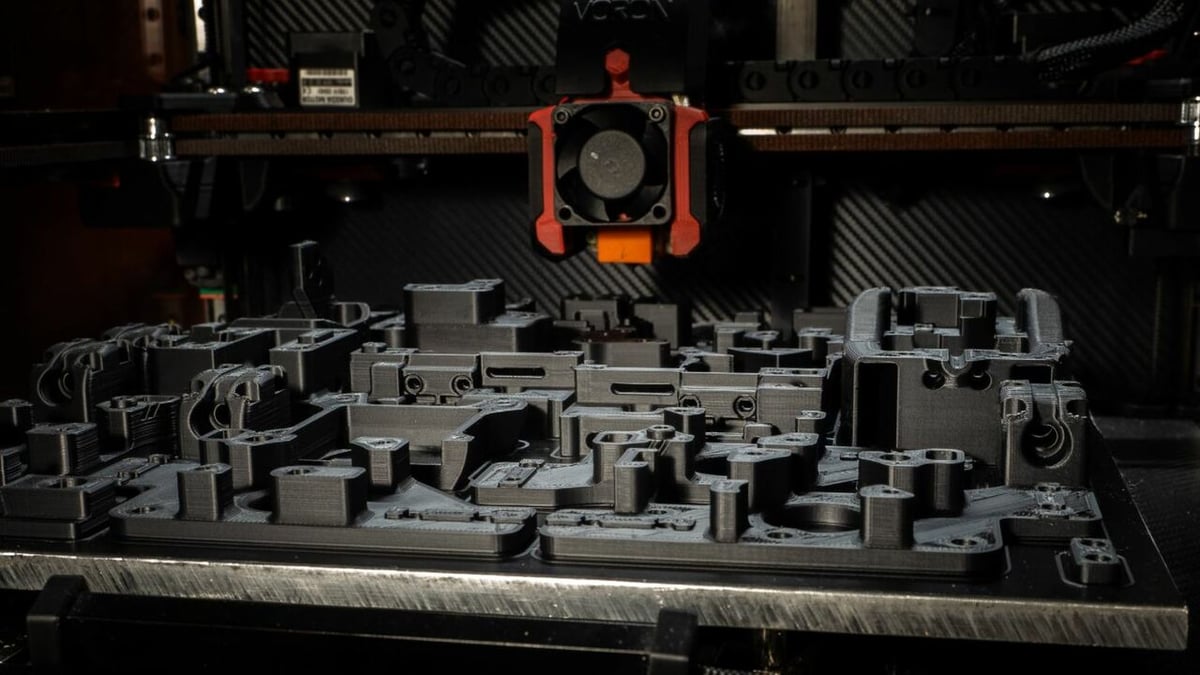

Where Print the Legend shows nascent companies building printers, perhaps our 2024 redux would instead show the individuals and communities developing their own better printers. Voron Design, a project founded by Maks Zolim, is one of a handful of projects at the forefront of DIY 3D printer design; chasing blistering speeds and performance while implementing features not found on consumer machines until, often, much later. Voron itself even inspired spin-offs in pursuit of peak performance 3D printing. One, AnnexEngineering, presides over a small handful of high-performance printers named after arduous mountains and challenges users with its SpeedBoatRace – the 3D printing of a Benchy, the ubiquitous “first” print for many, as quickly as possible to a set list of print parameters whilst maintaining some semblance of quality. This need for speed is certainly rich enough for its own thread.

One core difference we can see between now and 2014’s personal 3D printing landscape is your ability to find and create models. At the time, the first name in 3D model repositories was MakerBot’s Thingiverse, which provided a simple (and memorable) place for users to share their printable creations. While it remains the most searched 3D model repository today, having survived MakerBot’s reputational bumps and scrapes (plus its own controversies and performance issues) to get a revamp as UltiMaker Thingiverse that restores its simple and slick utility, it has competition now. For one, the rapid evolution of Prusa Research’s Printables, which uses a reward-points system to encourage user interaction, offers dedicated brand-specific pages that claw towards a future where spares and mods for the things you buy can be easily found and, crucially, printed on your personal printer.

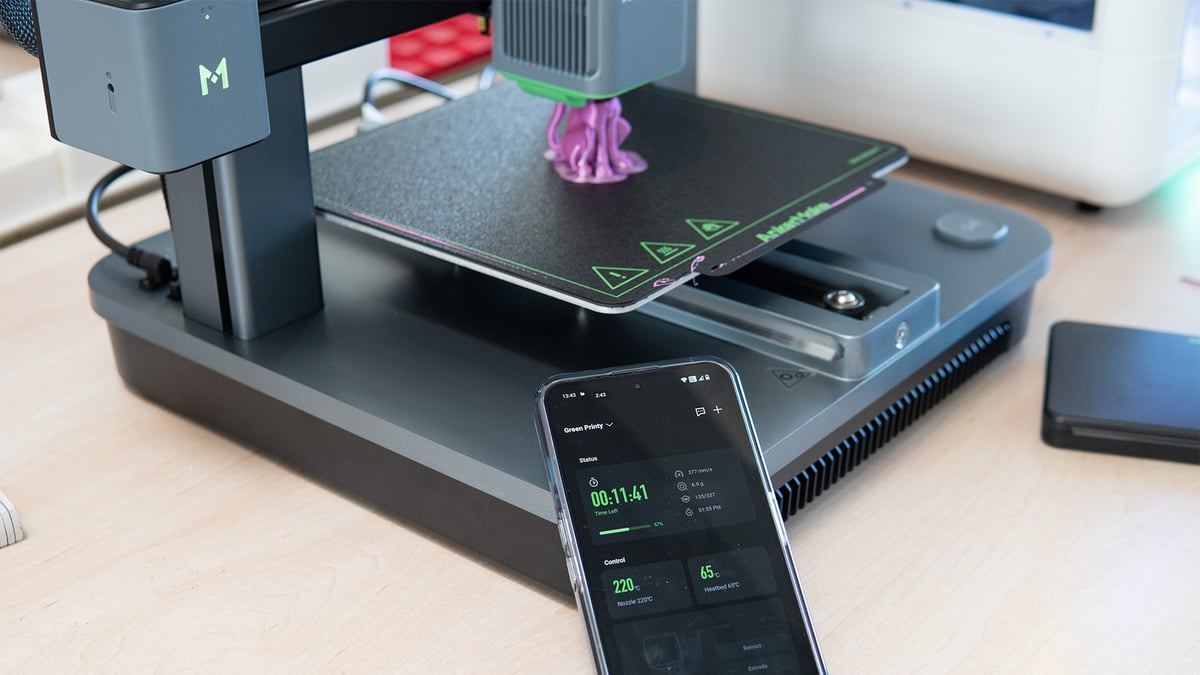

Niche-specific repositories cater to diverse 3D printing audiences, too, with MyMiniFactory effectively covering tabletop gaming and manufacturer-operated sites offering deeper integration with the hardware. Newer manufacturers like Bambu Lab and AnkerMake are two pointed examples of brand-specific integration that let users find a model and fire it directly to their printer. This is perhaps the closest we get to the vision of a 3D printer as an appliance in every home that seemed so inevitable for some in Print the Legend.

Ten years is a long time in tech, and while the printers (and prints) look largely the same, desktop 3D printing is having its heyday; 3D printing has never been cheaper, faster, higher quality, or more accessible. Just as the documentary covers a select few during a fixed point in time, so too does this article. For Reichental, the crucial story to tell of desktop 3D printing today and its challenge for tomorrow is that “…with the arrival of AI, by 2030, there will be two kinds of AM companies: those who successfully adopted AI to their advantage and those who are out of business.”

For Lobovsky, there are two key plot points of the last ten years that deserve focus. The first is material science, which has boomed in terms of the possible combinations and properties available compared to ten years ago. “The growth there has made 3D printing so much more valuable to so many different groups”, he explains. The second is less conservatism in physical production. “In the last few decades, software creation has gotten so much easier, but making physical things is still too messy, frustrating, time-consuming, and expensive. This severely limits how people approach hardware development, making them more conservative. This mostly comes down to tools — software tools are fast, versatile, and inexpensive, so software developers experiment much more. Manufacturing technology is still too rigid and expensive, but 3D printing has offered a way for hardware developers to move more quickly and freely.”

Print the Legend is available to stream on Netflix and remains well worth a watch for a fun glimpse at a snapshot in desktop 3D printing’s history.

There is so much more we could have covered above. What do you think has been an integral part of the fabric of desktop 3D printing in the last 10 years? Or what will be important in the next 10? Let us know in the comments.

You’ve read that; now read these:

License: The text of "Print the Legend is Ten Years Old: Here’s What’s Happened Since" by All3DP is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Stay Informed, Save Big, Make More

Stay Informed, Save Big, Make More