We talk to Open Bionics co-founder Samantha Payne about 3D printed prosthetics, turning kids into superheroes, and the value of open source.

Before 3D printing technology entered the medical realm, prosthetics devices were usually seen as expensive, lacking function, and aesthetically unpleasing. However, when former tech journalist Samantha Payne met robotics engineer Joel Gibbard back in 2013, the duo decided to fuse their ambitions to help those with physical disabilities.

Together, the following year, they started the UK-based robotic arm and prosthetics firm Open Bionics. Not only has the startup managed to greatly reduced the price of prosthetics, making them more accessible to all, they’ve also made assistive devices cool to wear, especially for children.

In the past, Payne and Gibbard have collaborated with Disney to create superhero-themed prosthetics, allowing kids to turn their disability into an attachment they can be proud of. The bionic hands are based on the characters from films like Iron Man, Frozen, and Star Wars. Following in line with their focus on accessibility, the startup is also fully open source, which has helped fuel their global community.

After winning £100,000 in funding from the Small Business Research Initiatives scheme, Open Bionics recently launched an National Health Service (NHS) trial for children living with physical disability. This six-month trial will showcase the feasibility of their technology and product.

Open Bionics has also put their efforts towards the field of robotics, recently unveiling the Brunel hand. This fully articulated robotic hand has 9 degrees of freedom and 4 degrees of actuation. It can be programmed using the Arduino and offers impeccable grip and functionality.

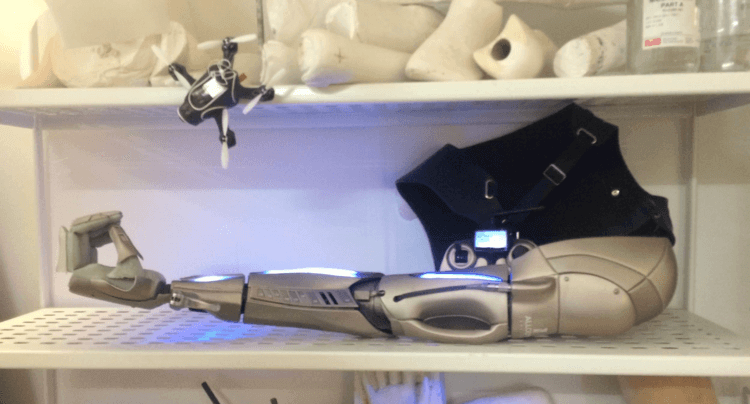

All3DP recently sat down with Samantha Payne at the CUBE Tech Fair in Berlin. While the company’s impressive Deus Ex-themed robotic arm was on display, we talked about the production of prosthetics and robotic arms, transforming amputees into superheroes, the ongoing NHS clinical trial, and more.

Q: How did Open Bionics first get started?

Joel and I decided to team up and build Open Bionics because I was thinking about robotic hands in a more wearable tech way. Joel was thinking of robotic hands as a medical device, clinical. I was thinking of it like, I wouldn’t want to wear that because that looks really ugly in its current form factor. Why wouldn’t you want it to be pink or glittery? If I want to wear it, I want it to look cool. That’s how we started. That’s where the idea started. It’s how we build prosthetics.

From that – that was obviously very early-stage thinking – we got in a room with a group of amputees and asked them loads of questions around prosthetics, pain points, mechanical experience, insurance. From the moment that you either bond without limb, what is the process that you go through? What’s the journey you go on to get a limb? Or, if you have a traumatic amputation, what happens then? We got tons of feedback from hundreds of amputees. We saw that 3D printing could enable us to make devices a lot faster and a lot cheaper, which meant a lot more people could access them. That was the main push to do this.

Q: You have that whole connection with Disney and focusing on younger kids. Can you talk about how you connected with them and the importance of giving a sense of personality to these prosthetic devices?

Yeah, of course. When we did this co-creation methodology, this co-design with amputees, out of these amputee workshops from kids came the idea of “I want to look like Spider-Man.” In fact, there was a little kid named Alfie from Ireland who we spoke to. The first thing he asked for was a Power Ranger hand. We were like, oh, how were we going to get him a Power Ranger hand? At the time, there were people online making super hero hands, but they weren’t official and we were really worried about copyright and ripping off people’s designs without crediting them.

We went to Disney and told them we wanted to build real super hero hands for kids who don’t have them. We want them to be exactly like they appear in the movies. We want to make replicas and give kids like Tony Stark’s Ironman hand to take to school. They really loved the idea. That’s how it got started. We worked with their artists and collaborated on design ideas. I think the reason why amputees really love it is because in terms of design, they’ve been neglected for a really long time. There’s not much at all being offered for them. Having good design increases limb adoption rates.

It helps them feel embodied so they adopt the limb faster. It’s their limb, rather than just something that they’ve been told to wear. There’s a sense of pride in it. Suddenly, your prosthetic isn’t a medical device that you have to wear. It’s something that you really enjoy, something you’re proud of. It expresses your personality. It’s something that makes your friends jealous. That’s the biggest feedback we’ve had from all of the people who’ve tried our devices is that when they get to show their family, all of the family is like, “Oh my god, that’s so cool. I want one.”

It kind of spins around the stigma around disability, where people automatically go to a pity mode. It’s not like that with these designs that we’ve seen.

Q: What are some of the advantages that 3D printing offers both prosthetics and the overall medical field?

3D printing is awesome for healthcare because it can be localized. You can take it anywhere. You can print remotely. You could have really cheap affordable 3D printers in developing countries or low-income countries send files across the web and print locally. It’s super important and will be much more important as time goes on. Printing, although everyone who does 3D printing says, it’s so slow, but it’s not. It’s actually really fast compared to other methods. And it will get faster, so that’s really good.

Bio printing is going to be really big in healthcare. Stem cells, skin cells, printing organs and limbs, even limbs, I think. I’m really thinking that will be happening. That’s really life changing, industry changing, I think, for certain.

Then you have scoliosis braces. You have wrist braces for broken bones. All of these devices have so many different benefits. I would take me a really long time to go through. It’s faster and cheaper to make and you can do it locally. Also, it helps the limb to breathe. It’s not going to get sweaty. You can also mold the splint in the right pressure areas really easily and you can thermoform. Each of these areas have tons of different benefits. There’s also 3D printing in dentistry now, which is super cool.

Some people are scared of new technologies. They’re scared of 3D scanning and 3D printing. They think it’s going to lead to job displacement so you won’t have any many clinicians in the hospitals. There needs to be loads of education around 3D printing and healthcare and job safety. No one’s trying to replace anyone. We’re just trying to make the experience better for patients.

Q: Can you talk about the technology that you currently use and the post-processing after the print?

Yeah. We have been using, at the moment, mostly Ultimaker 3. We’re using Lulzbot for our first bit of prototyping. Then we quickly change to Ultimaker 3 because we found that their printing was much more reliable and faster. They also brought in a dual extruder, which is awesome. They allowed us to print flexible materials before anyone else did at a really cheap price. That was really cool. So we’re using Ultimaker and we’ve got a BQ Witbox. That’s cool because it has an enclosed chamber to protect the environment, which will be a brilliant point as we get more and clinical.

Q: What’s the development process behind these prosthetics and robotic arms, from design to 3D printing and even into post-processing?

At the moment we’re using a 3D scanner as the central structure. We’re testing that in a clinical setting with clinicians this month. Hopefully the scans will pick up enough data so that doctors can make really decent sockets from it. Then from the occipital scan, we 3D print using Ultimaker and Witbox with Cheetah filament from Fenner Drive.

We’ve been testing a ton of different ways of making smooth prints. We’re still experimenting that. We’re trying to find a way that we can do it in-house without using SLS printers because it gets way more expensive and not the point of our goal to make prosthetics affordable. We’re trying poly smooth. We’re trying lots of different ways of making the devices smoother. At the moment, what we’re trying to do is cut down the amount of detail that we have on our designs so that post-processing is no time at all. That’s something that we’re working on.

Q: Can you talk about why the open source community is such a major part of your business and how that has helped drive Open Bionics forward?

Yeah. Wendell and myself, we decided that there were so many problems in the prosthetics industry after we spoke to amputees. This is actually really bad. One of our missions was to accelerate the growth of the technology. The best way we could think of doing that was by being open source and allowing other researchers to basically use our platform so that they could make their own moves forward much faster. We did open a developer forum and we had a few people quite interested in that. It sized down a lot recently.

But mostly we see researchers in big institutes across the U.S. using our designs in labs. They use it for anything from testing new control systems – making better EMG systems and using machine learning to make way more dexterous hands. We are seeing a lot of progress in prosthetics. Our device is being used to enable that progress. The biggest value we have seen is from the researchers telling us what they’re doing – how they’re using it and how they’re pushing the tech forward, and from amputees who have downloaded the designs, 3D printed them and then shown us the changes that they’ve made and suggestions for changes that we should do. Those are the biggest values that we’ve seen.

Q: Can you talk about the advances with the Brunel robotic hand and what the idea behind that was?

The Ada hand was a really interesting phase for us because we had never sold a product before. It was interesting because we hadn’t thought through well enough how we priced it. We actually priced the Ada hand too cheap for us to build it and ship it and assemble it and box it up and then deal with supports. Lots of people had questions because it was open source as well. People were like, can you help me change the software? We hadn’t really built into the price our engineering time to support people with their projects. With the Brunel, the main improvements are the strength – it is way more stronger than the Ada hand – and has a much better grip.

When researchers are basically testing with picking up glasses or tiny objects like screws or bits of Lego, this is way more accomplished than the Ada hand. The Ada hand could pick up bigger objects and hold them, but this is going to hold very small and large objects with ease, and heavy objects. We wanted to develop this hand because it would have a greater range and would allow researchers to test more activities.

Q: Thinking robotics and 3D printing, besides just helping with new prosthetics, do you see this kind of thing having a future in fashion and art and those fields at all?

That is a bold future. I think we are decades away from having a hand that can match the human hand in terms of functionality and these bionics look cool and they are going to look super sweet in 5 to ten years. They’re going to look amazing. I don’t think they’ll have the senses, the touch that we have and the strength and flexibility. When we get to that point, I can totally see that happening. I don’t think there’s a reason why that wouldn’t happen. It’s just a body augmentation.

Q: Can you talk about the idea behind this Deus Ex-inspired hand?

This is a 3D camera so you can control the hand. The connection is that. That design there and this here is this guy’s arm. So it’s an exact copy design of his arm. We worked with the artists at Deus Ex to create this limb. We made another one called the Titan arm. The point was to make these cyber-punk, high-fashion devices that people really enjoyed wearing. It just basically empowers the person who’s wearing it.

Q: What does Open Bionics have in store for the near future?

We’re in the middle of a clinical trial right now or this month we have an open trial with ten kids aged 8 to 18. That’s really big for us. I think it’s big for the industry because it’s the first time a 3D printed wearable medical device has ever been tested in a clinical setting and prescribed to patients. It’s the first time a multi-grip, advanced bionic arm is going to be given out through the National Health Service in the U.K. It’s two big changes. That, in itself, is a big step change. After that, we’re going to be selling these devices in Europe and then hopefully in the beginning of next year in the U.S.

From then on, we’ve already signed to research and develop different products like other assistive devices. When we started on bionics, we were focused on just making bionic hands. Now that we’ve really dived into the realm of disability and robotics and assistive devices, we can see different applications for our technology. Robotic gloves for people who’ve had strokes, really cheap, affordable exoskeletons, and even full-body exoskeletons. Then lower limb prosthetics. There’s a ton of areas and directions we can go into. I think it’s going to be a really interesting journey for us once we’ve nailed the bionic hand bracket.

License: The text of "Open Bionics Samantha Payne Helps Disabled Kids Become Superheroes" by All3DP is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.